Since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the associated mobilization, according to various sources, several hundred thousand to almost one and a half million citizens have left the Russian Federation—about 700,000 of them in the first year of the war. The Kremlin claimed that this was a fabrication, but did not provide any data of its own.

Statistics for the period from Russian President Vladimir Putin's first term to 2019 show that the 1.6 to 2 million citizens who left the country during this period were ethnic Russians with higher education.

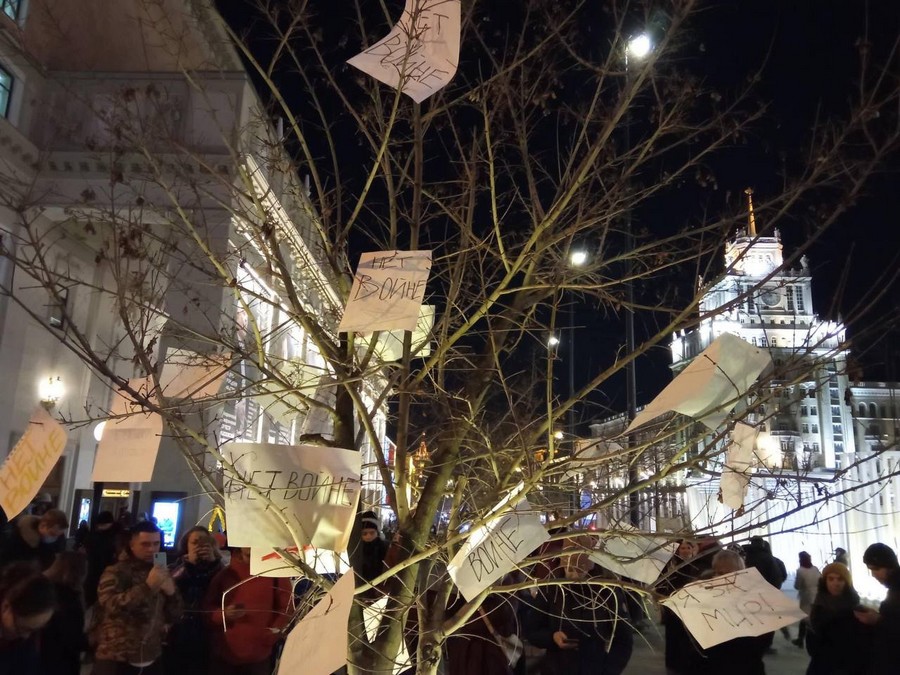

The main reasons for emigration include the desire to avoid mobilization and war altogether, as well as state repression of citizens with anti-war and thus more or less dissident attitudes. The current age and ethnic structure of emigrants from Russia may therefore differ significantly from that of the pre-war period.

The most important centers of Russian emigration are primarily countries that have closer ties to Russia and where it is not difficult to legalize one's status, i.e., to enter without a visa, to reside legally in the country thanks to a Russian passport, and, if interested, to obtain a temporary and later a permanent residence permit, and in exceptional cases even citizenship.

These are primarily Armenia, Kazakhstan, Georgia, Turkey, and Serbia. Some emigrants prefer countries with a more democratic domestic political climate, which also do not extradite Russians who are being prosecuted for political reasons to Moscow.

Dream and reality

In this respect, the United States of America has long been the most attractive destination, perceived by Russians as a safe haven for those facing political persecution.

According to the US Customs and Border Protection, more than 57,000 refugees from Russia crossed the US border in the first year of the war – from October 1, 2022, to September 30, 2023 – half as many more than in the same period last year.

One of the first measures taken by the new US President Donald Trump immediately after his inauguration on January 20, 2025, was to suspend the American refugee admission program, initially for 90 days.

The president declared a state of emergency on the US-Mexico border and deployed the military. Paradoxically, however, it was not migrants from Latin America, who most frequently crossed the border illegally, who were under the greatest pressure, but citizens of Russia and other post-Soviet republics.

However, the situation for Russians had already deteriorated significantly under former President Joe Biden. According to the New York Post, citing a leaked service document, the US Border Patrol was allowed to admit migrants from hundreds of countries into the country.

However, a different rule applied to citizens of Georgia, Moldova, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Russia: adult citizens of these countries were to be immediately deported.

Although, according to official statements, this procedure was not supposed to apply to asylum seekers who had used the CBP One mobile immigration app to enter the country legally, immigration lawyer Yulia Nikolayeva confirmed to the Russian project Republic that this was not so clear-cut in the case of Russians.

Prisons for Russians

According to Nikolajeva, since June 2024, Russian asylum seekers have been placed in immigration prisons from which they have not been released, while non-Russian asylum seekers have been released from prison immediately and have been able to prove their right to refugee status while remaining free.

Immigration prisons in the US are one of the most controversial aspects of the country's migration policy, and conditions of detention are increasingly criticized.

Detainees are housed in overcrowded rooms, where poor hygiene, inadequate health care, and insufficient nutrition are often prevalent.

Reports from Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International point to unsanitary conditions and physical violence. In the centers where Russian refugees are also held, psychological and physical violence against minors, among other things, occurs.

The New York Times has found that since the beginning of Trump's new term in office, the tactic of family separation has increasingly been used as a means of forcing illegal migrants to leave the US.

Border authorities offer Russian families seeking asylum the choice of either leaving the country with their children or staying in a migrant camp, with the children being placed in children's homes or foster families.

Yevgeny and Yevgeniya were affected by this policy in May of this year. After refusing to return to Russia, where they said they faced prosecution, the parents were separated from their 8-year-old son Maxim.

The son was taken by the authorities to a home for neglected children, while the parents were sent back to a migration center in New Jersey.

The new regulations issued by the US State Department on September 6 state that Russians who wish to enter the United States on a tourist, student, or work visa can no longer apply for one at any US diplomatic mission.

The new rule is that applications can only be submitted in Astana (Kazakhstan) or Warsaw (Poland). Other consulates can only be contacted in exceptional cases – for example, in the context of visa applications for humanitarian, health, or political reasons.

The bitter aftertaste of home

On August 27, the US authorities expelled 30 to 60 Russian citizens from the country. Among them were several people who, according to their statements, were threatened with political persecution in their home country, but also a member of the Russian Federation's armed forces who was charged in Russia at the time with desertion for leaving his unit without permission.

As there are currently no direct flights between the United States and Russia, the expulsion took place via a third country – with a stopover in Egypt.

The plane carrying the deported Russians landed at Domodedovo Airport in Russia. Russian border officials subjected the returned citizens to lengthy checks and interrogations – so far, it is known that one person was detained and several others were released after signing a declaration not to leave the country.

According to Vladimir Osechkin, founder of the Gulagu.net portal, border officials interrogated all returnees from the US, subjecting them to psychological pressure and, in some cases, brute force. According to Osechkin, seven deported Russians face criminal proceedings.

Refugees in the US with Russian citizenship who are facing deportation have virtually no way of avoiding expulsion. Attempts to change flights when transferring from the US to Russia end in the use of force.

Russian opposition politicians in exile have sent a letter to Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney asking him to grant asylum to Russians who are being deported from the US to Russia.

The letter was signed by Yulia Navalnaya, the widow of opposition leader Alexei Navalny, and former political prisoners Vladimir Kara-Murza and Ilya Yashin—the three most influential representatives of the civil opposition.

“People who have fled the Kremlin's repression and Putin's prisons end up in American prisons,” the Russian opposition representatives summarize in their letter.

Štandard contacted Ilya Yashin's public reception office in Berlin, which currently advises Russian citizens against migrating to the US.

"People there are often placed in immigration detention centers, where conditions are unacceptable. The US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) regularly separates families – one spouse may remain behind bars while the other is released or transferred to another prison," Yashin's office confirmed to Štandard, corroborating reports from the US.

According to the office, decisions on whether to grant or deny a visa are protracted and often take months or even years, during which Russians live in constant fear of deportation.

The Old Continent

The situation with humanitarian and other types of visas for Russians is better in the countries of the European Union than in the US, but it is still not ideal.

This seems particularly surprising given the statements made by European leaders about the need to support Russians with opposition views.

In a February 2024 European Parliament resolution on the death of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who was imprisoned by the Kremlin regime, MEPs clearly stated their position: “The EU and its member states should express their full support for independent Russian civil society and the democratic opposition.”

One of the first countries to grant asylum to Russian defectors, even without papers, was France.

According to the Schengen News portal, Germany has issued humanitarian visas to more than two thousand Russians in the first two years since the full-scale invasion began.

However, according to the public reception center Ilya Yashin in Berlin, Germany is not the best choice.

"While in Italy or Ireland the success rate for issuing visas is 70 to 80 percent, in Germany it is only 7 to 11 percent. LGBT people in particular have an almost certain chance of obtaining a visa in Germany. It also helps if the applicant speaks the language of the country for which they are applying for a visa – this significantly increases their chances," Jashin's office in Berlin told Štandard.

In addition, according to the office, Germany has temporarily suspended the issuance of humanitarian visas – it subsequently stated that issuance had resumed, but this has not yet happened.

“In the Netherlands, the situation regarding the issuance of visas is unclear due to the formation of a new government. The Netherlands has already helped many Russian emigrants, for which we are grateful, but the anti-immigration rhetoric of a possible new government could result in laws that also affect migrants from Russia, not just those from Africa, Asia, or Latin America,” the office explains.

In the first days of the Russian mobilization, the Czech Republic, Finland, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia declared that they would not grant asylum to Russians who want to evade service in the Russian army and thus the invasion of Ukraine.

On June 8, 2025, a meeting on the rights of Russians critical of the regime took place in Brussels. The meeting was attended by MEPs, human rights activists, and representatives of the Russian civil opposition: Yulia Navalnaya, Vladimir Kara-Murza, and Ilya Yashin.

According to Deutsche Welle, the discussion began with the screening of a two-minute video in which deserters and other Russian citizens trying to leave the country spoke about the difficulties they faced in EU countries.

They also spoke about their fear of being forcibly returned to their home country. “We do not expect special treatment—we ask for safety, dignified treatment, and the right to live without fear,” the Russians said in the video.

In connection with visa restrictions, the Czech Republic is worth mentioning. Politicians in that country are known for their statements and actions toward Russia, although this is more often felt by Russian emigrants than by the Kremlin regime.

In addition to the collective responsibility of Russians for the invasion of Ukraine, they often spoke of the need to fight against the regime and avoid mobilization by all means.

However, Prague was one of the first countries in the EU to deny asylum to Russians who had fled mobilization.

Foreign Minister Jan Lipavský told Reuters that those who “leave Russia only because they do not want to fulfill their duties imposed by their own government do not meet the criteria for granting a humanitarian visa.” Russian citizens who were denied such a visa joined the ranks of the invasion army in Ukraine.

The announced support for the Russian and Belarusian opposition was ultimately limited to the “Občanská společnost” (Civil Society) program, with a quota of 500 visas per year for journalists, human rights activists, and activists from both countries.

Different under the Tatras

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Slovakia has taken a more balanced stance on the issuance of visas.

In response to the mobilization, Bratislava ruled out the possibility of issuing humanitarian visas across the board due to efforts by Russian citizens to evade conscription, but the then spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Juraj Tomaga, added that each application would be considered individually.

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion, Slovakia has not once suspended the possibility of obtaining a visa across the board – Russian citizens who work or study in Slovakia or who wanted to reunite with family members already residing in Slovakia were able to enter the country. These were type D visas.

The issuance of tourist visas to Russian citizens resumed on August 28 this year, as reported by the BSL International visa center.

However, impressions of applying for a Slovak long-term visa in Moscow were not always positive. Štandard spoke with Russian student Alexandra, who was supposed to fly to Bratislava to study in January 2023.

“On the day I submitted my visa application, the embassy staff refused to talk to me – they accused me of Russia's invasion of Ukraine and said that my life would never be the same again. They told me not to even try to come to the EU,” Alexandra recalls.

The Slovak embassy did not accept the documents that day. Alexandra had not felt safe in Russia for some time, as her friends and family knew that she had taken part in a protest rally against the Russian invasion in Moscow – the Slovak embassy's refusal to accept her documents did little to reassure her.

“The matter only got rolling after I wrote a letter to the Slovak Ministry of Education complaining about the open discrimination based on my nationality,” explains the young student.

Alexandra finally came to Slovakia and is currently continuing her studies at a Slovak university. However, not every applicant was so lucky.

Natalija, a doctor from the Rostov region, received a job offer from a healthcare facility in the Košice region.

"I checked the visa requirements in advance on the embassy's website. I brought my diploma with an apostille, which had been translated into Slovak [it was submitted to the editorial office of Štandard, editor's note], but the embassy staff did not accept it and said that it was an unnecessary document and not required for the issuance of a visa," Natalija told Štandard.

She went on to explain that the Slovak embassy ultimately did not issue her a visa, precisely because of the missing diploma, which she had not taken with her to submit the documents after the initial consultation.

“The requirements for a visa apparently changed depending on the mood of the employee and his subjective wishes,” said the young Russian doctor.

As the public admissions office Ilja Jashin in Berlin explained to Štandard, each case is individual and neither the approval nor the rejection of a visa can be guaranteed in advance.

“Ultimately, an important role is played by how well-known a person is, what their CV looks like, in the case of asylum applications, the likelihood of persecution in their home country and the possibility of proving this risk, and last but not least, the support of local non-governmental organizations and lawyers,” Yashin's office summarizes.

He reminds Russian migrants that there is no general recommendation for the lack of transparency and complexity of the asylum procedure in individual countries.

You simply have to soberly choose the country in which you want to legalize your status as a Russian migrant and, above all, not hope that the procedure will be quick and easy.