On September 17, the lower house of the Russian parliament, the State Duma, approved President Vladimir Putin's proposal to withdraw from the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

"European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment [ECPT, editor's note] of November 26, 1987, and Protocols No. 1 and No. 2 of November 4, 1993, signed on behalf of the Russian Federation in Strasbourg on February 28, 1996, are hereby terminated," the approved proposal states.

State Duma Chairman Vyacheslav Volodin said that Russia's membership and work in the Council of Europe's Committee Against Torture (RE) “is being blocked by the Council of Europe itself, which has not allowed the election of a new committee member from Russia since December 2023.”

“Complaints regarding ensuring Russia's representation are being ignored, despite the principle of cooperation enshrined in the European Convention,” Volodin added. Russia was expelled from the Council of Europe shortly after the start of its invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment was adopted in 1987 and is one of the Council of Europe's most important conventions.

It allows members of the Committee Against Torture to monitor detention facilities in member states. The committee focuses in particular on prison overcrowding and improving detention conditions.

Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin proposed to Putin in a decree on August 26 that the State Duma propose withdrawal from the convention. A formal withdrawal date had not yet been set at that time.

Just a formality

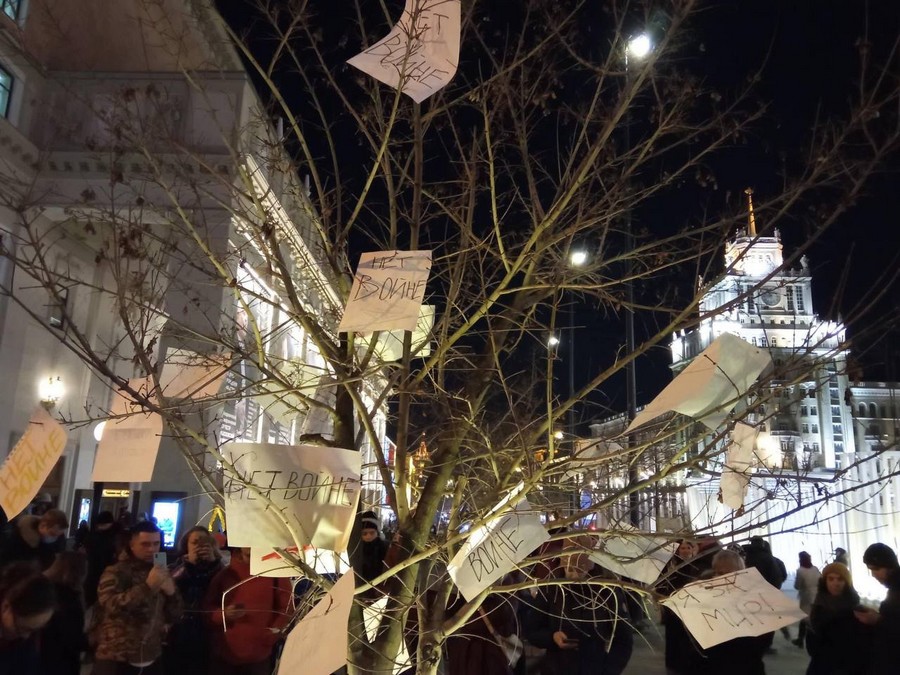

Politico magazine wrote back in August that Russia's withdrawal was primarily a symbolic move, given the massive human rights violations committed in the country. According to the report, the poor human rights situation worsened after Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Politico pointed out that the Kremlin primarily tortures political prisoners in prisons. On February 16, 2024, opposition leader Alexei Navalny died in a penal colony in the city of Charp, which lies beyond the Arctic Circle. His wife Yulia stated on September 17 of this year that her husband had been poisoned in prison.

According to her, people close to Navalny managed to smuggle biological samples abroad, where they were analyzed by two independent laboratories. Both came to the same conclusion: Navalny had been poisoned.

However, the test results have not yet been published by the aforementioned institutions. Navalny's wife accused Western politicians and the management of the laboratories of preventing the publication for political reasons.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said he was not aware that Navalny had been poisoned in prison. The city court in the Russian city of Salechard refused the day before, on September 16, to initiate criminal proceedings on suspicion of murder.

Navalny's mother, Lyudmila, had already requested the initiation of proceedings the day after Navalny's death, on February 17, 2024. However, her request was repeatedly rejected. The politician's mother appealed the rejection to the court. The court in Salekhard ultimately rejected her appeal.

In recent years, Russian nationalist Maxim “Tesák” Marcinkevič, Ukrainian journalist Viktorija Roščynová, and a dozen other people have also died in Russian custody and prison under unclear circumstances.

The extent and level of police brutality increased in connection with the suppression of anti-war sentiment. Russian citizens were subjected to violence during their arrest or later in custody: these were cases of beatings or rape of men and women.

However, brutality in prison was no exception in the 2000s. A vivid example of this is the death of Russian lawyer Sergei Magnitsky in 2009 during the presidency of the current Deputy Chairman of the Security Council of the Russian Federation, Dmitry Medvedev.

Magnitsky was accused of tax evasion after he published his findings about a group of high-ranking government officials who had committed fraud at the expense of the state budget and the Hermitage Capital fund, embezzling several billion Russian rubles.

However, the lawyer received neither a verdict nor an acquittal: after a year in custody, he died under unexplained circumstances.

On December 14, 2012, US President Barack Obama signed the so-called Magnitsky Act, which legitimized the imposition of financial and visa sanctions against Russian officials responsible for human rights violations.

The Russian response to the passage of the American law was the withdrawal of charges by the Russian prosecutor's office on December 24 of the same year – the charges had previously been brought against the only suspect in Magnitsky's murder.

War torture

Experts commissioned by the UN Human Rights Council claim that Russia is using sexual torture against civilians—both women and men—as part of a deliberate and systematic intimidation campaign in the occupied territories of Ukraine.

They have submitted a dossier to Moscow detailing ten cases of torture of Ukrainian civilians during the Russian occupation.

All ten civilians were subjected to “repeated electric shocks” by the Russians, including in the genital area, and they were beaten and kicked, according to the experts' statement.

In addition, the Russians blindfolded the prisoners and subjected them to situations in which they were led to believe they would be drowned or executed.

“These individual allegations, which reflect the experiences of four women and six men, are truly horrifying,” said UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Alice Jill Edwards.

However, she warned that this was only “a small sample of a broader, well-documented pattern” and that the cases cited involved assaults of a clearly sexual nature, including rape or threats of rape.

“It is becoming increasingly clear that the Russian Federation's deliberate and systematic policy of torture in Ukraine also includes sexual torture and other forms of sexual cruelty, including against the civilian population,” the Special Rapporteur said.

Russia uses “torture to intimidate, spread fear and control the civilian population in the occupied territories of Ukraine,” the rapporteur said.

They called on the Russian government to explain the specific allegations mentioned in the report and to present measures it has taken to prevent sexual torture by soldiers. At the same time, they called for the immediate release of one of the victims who, in their opinion, is still being held in Russia.

Edwards, Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, also dealt with similar crimes committed by Israeli security forces against Palestinian Arabs.

In addition to the convention from which it has withdrawn, Russia is bound by several international conventions aimed at preventing torture.

These include the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and others.

The question remains as to the extent to which these provisions are applied in practice—both in Russia and in other countries that violate the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which was adopted by the United Nations in 1984.