Moldova has been a candidate for EU membership since 2022, and its citizens will vote on the composition of the new parliament on Sunday.

President Maia Sandu's ruling pro-European Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) has held a parliamentary majority since 2021.

According to the government in Chișinău, Russia is influencing the elections by spreading disinformation, preparing mass unrest, and buying votes. Moscow rejects these allegations and considers them unfounded, according to the Foreign Ministry.

Polls show that the PAS could lose its majority as opposition parties focus on voters concerned about the high cost of living, rising poverty, and a stagnant economy.

According to polls, the only real competitor to the president's party is the left-wing alliance called the Patriotic Bloc of Moldova (BEP), led by former president Igor Dodon. The alliance's logo is a Soviet five-pointed star with a heart in the center—inside which are crossed hammer and sickle.

A poll published on September 24 by the Idata agency showed that 24.9 percent of respondents would vote for the pro-European PAS, while the pro-Russian BEP achieved 24.7 percent.

On September 8, the BEP promised in its election program to lift sanctions against Russia, restore “strategic relations” with Moscow, and establish such relations with Beijing.

Analysts generally agree that the president's party's participation in a coalition government could hamper its efforts to bring Moldova into the EU by 2030. “Unfortunately, the PAS is currently the only influential pro-European force, so most EU supporters vote for them,” Vlad tells Štandard on the streets of Chișinău.

He criticizes the lack of other pro-European parties, as this plays into the hands of those who want to be “under Moscow.” In his opinion, this has led Moldovan society to equate the PAS with the European path.

“And when the PAS makes mistakes—which is not uncommon—it damages not only the party's reputation, but also the idea of European integration itself,” Vlad concludes.

Incidents before the elections

In the town of Hînceşti, on September 27, the police seized over 11,000 copies of the pro-Russian samizdat magazine Sare și Lumină (Salt and Light), which a local priest had distributed shortly after the church service.

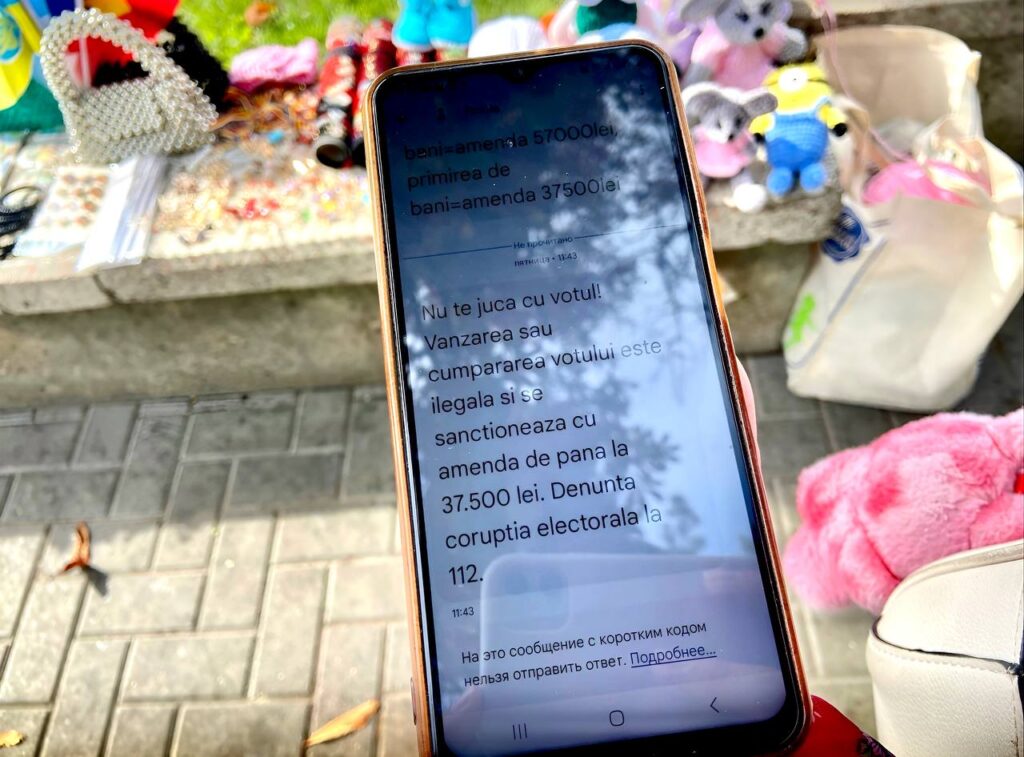

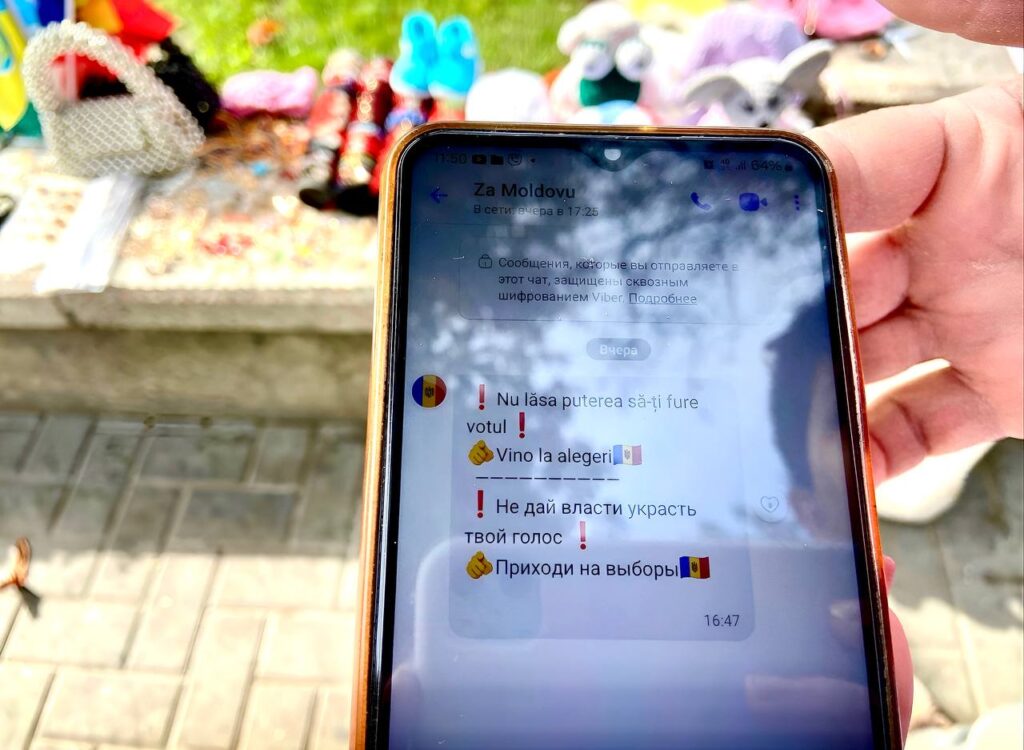

Also during the moratorium, several citizens report receiving text messages from Indonesian, Russian, and other foreign phone numbers. The messages urge people to participate in the elections so that “the government does not steal the people's votes.”

The hand of Moscow?

The BEP originally consisted of four political parties: the Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova, the Communist Party of the Republic of Moldova, Heart of Moldova, and Future of Moldova.

On September 26, the Central Election Commission banned the Heart of Moldova party from running on charges of financial fraud.

It did the same with the Greater Moldova Party, which, according to investigators, had used unreported funds and was also suspected of offering money to voters to influence the election results. Local representatives suspect that the party was acting as the successor to the banned party of exiled pro-Russian business magnate Ilan Shor.

Schor denies any wrongdoing but lives in Moscow. “Shor, Dodon, these left-wing lunatics – they're all cut from the same cloth. If they come to power, we'll dance to Moscow's tune. I have a wife, two beautiful children, and I don't want us to become like Transnistria – to the shame of our ancestors and descendants,” says Ion, speaking to Štandard near the polling station.

The street vendor of souvenirs of Gagauz nationality wants “the standard of living in Moldova to approach that of the EU.” Since she believes Sandu is not succeeding in this, she and her husband voted for Dodon's alliance.

“But I didn't really need to vote – Sandu will surely manipulate the results to suit her,” the Gagauz woman tells Štandard. Like the president's party voters, she does not want to be photographed – but she has agreed to have the text messages on her cell phone photographed.

“People are afraid to speak out, and I am afraid of the election results. We have visited dozens of communities and explained to people what is at stake... We can only hope that our window to Europe will not close after today,” Carolina Bogatiucová, former office manager of the Minister of Foreign Affairs and European Integration Nicu Popescu, told Štandard.

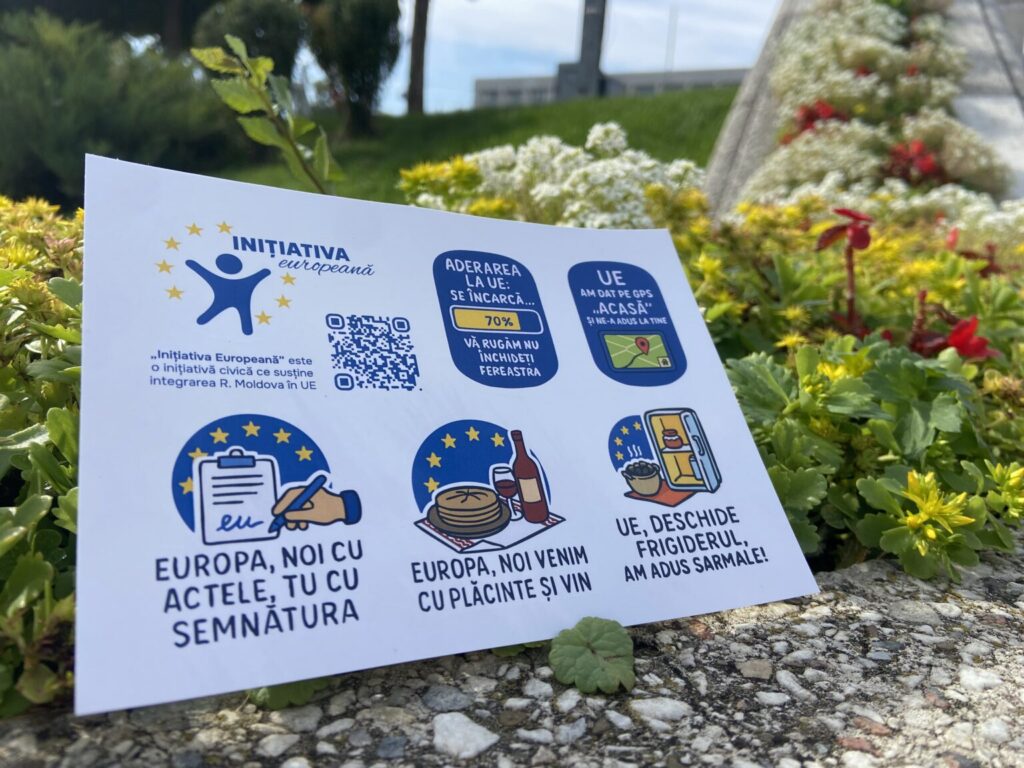

At the time of reporting, she and other activists were distributing a set of stickers with Moldovan motifs related to European integration. “Pro-Russian representatives, whom I will not name due to the moratorium still in force, are spreading Russian propaganda that anyone who wants to join the EU is against everything Moldovan, but that is a lie,” she says.

One of the stickers reads “EU accession is loading – 70% – please do not close window,” which indirectly urges people not to vote for Dodon's bloc.

Trained protesters

The Moldovan authorities carried out raids on more than a hundred people on September 22 who were linked to Russia's efforts to destabilize Moldova, according to local police.

The result was the arrest of 74 people suspected of having been trained in Serbia under the Kremlin's supervision to provoke violent unrest during the Moldovan elections and after the results were announced.

If Sanduova's party loses, Moldovan investigators say the protesters will demand the president's resignation. If her party wins, the protesters will claim that the election results were rigged.

Four days later, on September 26, Serbian police arrested two people who had been involved in training 150 to 170 protesters between July 16 and September 12. Belgrade did not disclose their identities or nationalities.

Chișinău and Tiraspol

The government in Chișinău does not control the entire territory of the country. The strip of land between the Dniester River in the west and the Moldovan-Ukrainian border in the east has been an unrecognized state with ties to Moscow since the 1990s, when Russia supported the separatists.

This is Transnistria, with its capital in Tiraspol, which Ion spoke about to Štandard.

Currently, the Kremlin has a “peacekeeping force” of around 500 troops stationed there. Moldovan Prime Minister Dorin Recean warned back in June that Moscow was attempting to influence the upcoming parliamentary elections in Moldova in order to install a government that would allow for a 10,000-strong increase in the military contingent in the Russian-occupied territory of Moldova.

Sandu claims that Moscow is spending “hundreds of millions of euros to finance political parties, bribe voters, and train young people for destabilizing activities.” According to the Moldovan president, this threatens the country's territorial integrity and independence.