President Donald Trump is pushing for lower interest rates with public statements, raising the question of whether this pressure is harming the central bank. The markets also expect to see money become cheaper more quickly in 2026, when the president will have a free hand in appointing a new Fed chair to replace the current one, Jerome Powell.

This assumption has even been factored into stock prices on the stock market. Several experts warn that such political intervention may seem tempting at first, but in the long run will only lead to higher inflation and slow growth.

Pressure from Nixon

Thomas Drechsel's (University of Maryland) analysis summarizes the historical experience with political pressure on the Fed. The analysis focuses in particular on 1971, when President Richard Nixon repeatedly (dozens of times) pressured then-Fed Chairman Arthur Burns to lower interest rates and stimulate the economy before the elections.

Drechsel compiled daily records of visits to the White House, which show that Nixon met with Fed representatives 160 times (Bill Clinton, for example, had only six such contacts). Today, however, Trump no longer needs personal meetings—he expresses his demands publicly and shares them daily on social media.

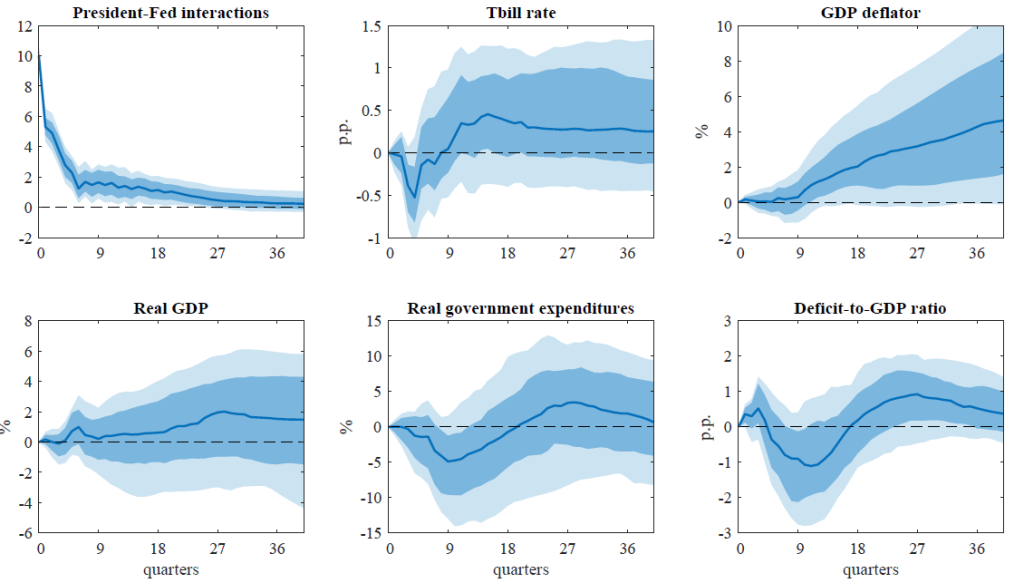

The study shows that when the president pushed for lower interest rates (a strong political “shock” of 10 interactions per quarter), short-term interest rates typically fell within 12 months. This has been partially confirmed recently: the markets already believe that the new Fed chair will quickly begin to make money cheaper.

However, the benefits of cheaper credit are only temporary: financial models show that political pressure leads to a more significant increase in price levels in the medium and long term. Drechsel's analysis found that this pressure increases inflation “strongly and sustainably.”

For example, half of the pressure in 1971 (within six months) led to a price increase of more than eight percent. In other words, a violent reduction in the price of money leads to a rise in prices: after ten years, consumer prices could be an estimated four to five percent higher than without this measure.

However, the biggest problem is not just inflation, but stagflation – the current rise in prices accompanied by an economic slowdown. The study shows that while the easing of monetary policy triggered by the pressure slightly boosts consumption (e.g., in housing construction), both businesses and households raise their inflation expectations. On this basis, they slow down their investments and job creation. The result is that inflation rises sharply, but economic growth slows down – exactly what experts refer to as stagflation.

In response to political pressure, investors in economic forecasts significantly increase their estimates for future prices (inflation rises according to analysts' estimates) and at the same time uncertainty increases. A large-scale study confirms that private expectations change diametrically when policy intervenes compared to normal monetary easing.

This rise in expected inflation directly leads to higher interest rate demands in the long term and increases the cost of credit (e.g., mortgages). The result is a slowdown in business investment and more cautious consumer behavior.

All responses from respondents in the studies are controlled for changes in other economic variables such as inflation, growth, deficits, and government spending. The lines show the median of the responses, the dark areas show the 68 percent confidence interval, and the light areas show the 90 percent confidence interval.

When politicians interfere with interest rates

Harvard economist Douglas Elmendorf (former director of the Congressional Budget Office) issued a stark warning: “If the Fed becomes an instrument of the president, we will likely have to live with higher inflation in the country for many years to come.” Joe Brusuelas of the consulting firm RSM also emphasized that annual inflation would rise to three to four percent if we let politicians dictate interest rates, and that middle- and lower-income groups in particular would have to bear the costs.

These views are echoed by Martin Eichenbaum of Northwestern University, who reminds us that an independent central bank makes its decisions “based on long-term economic goals—stable prices and sustainable growth—rather than short-term political gains.” He adds: “We don't want to return to the inflation of the 1970s,” i.e., to a situation in which the US found itself precisely because of excessive political interference in monetary policy.

Conservative analysts and historians point out that what we are seeing today is not a fairy tale, but a repeat of past mistakes. Lyndon Johnson simultaneously increased deficits during the Vietnam War and pressured the Fed to keep interest rates low – the result was the terrifying inflation of the 1970s. Nixon's pressure also left its mark on history: years later, practical economists accused him of blocking the Fed's anti-inflation policy for purely political reasons.