Since 1823, the United States has viewed the Western Hemisphere as its "backyard." They therefore exert pressure on South American countries that refuse to cooperate with Washington, the most recent example being Venezuela.

Throughout history, South American states have oscillated between hard-left governments and "right-wing" dictatorships. Only now are elected right-wing presidents coming to power in some of them, particularly in Argentina and Ecuador. It is Javier Milei and Daniel Nobou whom US President Donald Trump considers his allies – as do the world's media.

The bloody pendulum of history

The Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela is no exception to this rule. After the war of independence from Spain, led by General Simón Bolívar, the country became part of a larger entity known as Gran Colombia. The general later became president of what was formerly Upper Peru (now Bolivia, named in his honor), but internal tensions caused the breakup and multiple redrawing of borders.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Juan Vincente Gómez took office as president, whose rule ended only with his death in 1935. Although he did not officially govern, he was the supreme military commander and de facto dictator, who used his brother and others as puppet presidents.

One of the fighters against Gómez was Pedro Pérez Delgado, the great-grandfather of the later ruler who became the most famous president of modern Venezuela. Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías rode a wave of anti-American sentiment and anti-imperialism during his career, although his first coup attempt ended in failure and arrest.

However, his arrival marked the beginning of the so-called Fifth Republic, with his predecessor Rafael Caldera stepping down in February 1999 and Chávez immediately approving a new constitution. This also changed the name of the country from the Republic of Venezuela to the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela.

At that moment, Venezuela became a showcase for resistance to the neoconservative and warmongering policies of the US. Chávez entered the pantheon of revolutionaries alongside Bolívar and Ernesto "Che" Guevara.

During the presidency of Carlos Andrés Pérez, Venezuela experienced two coup attempts, both in 1992. The result was not only Chávez's imprisonment but also a harsh crackdown on human rights, including extrajudicial executions—the DISIP secret service allegedly murdered around 40 people.

Chávez himself became the target of accusations of "uninvestigated" human rights violations during the suppression of coup attempts in 2000 and 2004. The human rights index continues to decline, and organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Freedom House are addressing this issue. In 2008, the latter removed the country from its list of representative democracies.

In 2002, Chávez was briefly replaced by Pedro Carmona, but his government lasted only 47 hours. The "leader of the Bolivarian revolution" later used this as a pretext to push through the abolition of term limits in a constitutional referendum in 2009. As a result, he became head of state four times, although the last term ended after three months with his death.

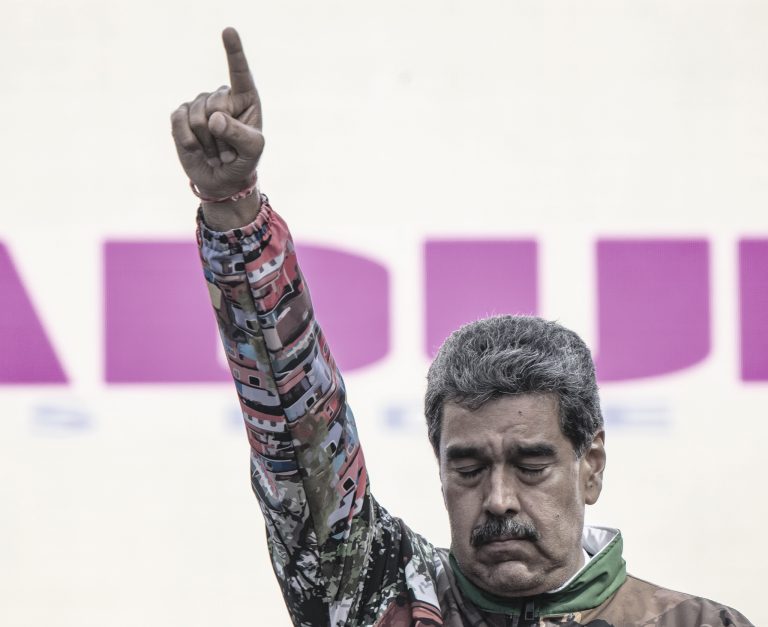

The welfare of ordinary people gradually began to decline, mainly due to price caps and export limits. Despite extensive social programs funded by oil revenues, the standard of living of Venezuelans declined, which, according to some observers, was reflected in the weak support for Chávez's successor, Nicolás Maduro. Maduro won only 50.6 percent of the vote in the 2013 elections.

Less than a year after Maduro took office, Venezuela experienced some of the most extensive student protests, which were led from the outset by one of the opposition leaders, Leopoldo López. The current opposition leader, María Corina Machado, also came to the fore in the demonstrations in the spring of 2014.

Semi-legal and paramilitary organizations supporting the Chavista government, known as colectivos, took action against the demonstrators. Similar organizations are currently active in the Colombian border region, where they terrorize local coca growers and other farmers.

The empire's response

The United States imposed its first sanctions on Venezuela and selected Venezuelan officials in 2005. In response to the suppression of protests in 2014 and 2017—which were in turn a reaction to the dissolution of the opposition-led parliament and resulted in dozens of deaths—the administrations of Barack Obama and Donald Trump approved sanctions against members of Maduro's government and security apparatus.

In 2024, President Joe Biden lifted some of the sanctions in order to use "soft power" to persuade Maduro to hold fair presidential elections. The Venezuelan leader allegedly rigged the election and became president for the third time – several Western countries and the European Union consider opposition leader Edmund Gonzalez Urrutia to be the winner of the election.

Back in 2018, after the elections at that time, the US government recognized opposition leader Juan Guaidó as the winner of the elections, who fled to neighboring Colombia after escalating repression. He is no longer very welcome there either, as leftist Gustavo Petro became Colombia's president for the first time.

The current Trump administration has imposed a 25% tariff on Venezuelan oil, whose exports to the US are gradually declining. Despite the widely known information about the "embargo on Venezuelan oil," American oil giants such as Chevron and Conoco have been buying tens of thousands of barrels.

At the end of January this year, imports from Venezuela accounted for less than 1% of total oil imports to the United States, or only 228,000 barrels per day.

In 1976, former President Carlos Andrés Pérez nationalized the entire Venezuelan oil industry and placed it under the control of the state-owned company Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). This was inspired by Arab producers who wanted to punish countries that supported Israel in the Six-Day War (June 1967). This move caused a global oil crisis in 1973.

However, this led to a rapid decline in living standards in the West, which only gave the United States an excuse to further intervene in South America—which it perceives as its "backyard" in the sense of the Monroe Doctrine of 1823.

Superpower games

China is currently the main importer of Venezuelan oil. In September of this year, Caracas surpassed the export threshold of one million barrels of oil per day – and 84 percent of these exports ended up in China, either directly or through third parties. At the beginning of November, however, exports plummeted by 26 percent from the five-year high in September to 808,000 barrels per day.

It is therefore clear that Beijing is increasingly encroaching on what Washington considers to be "its" territory. Like Russia, Xi Jinping's government not only declaratively supports Maduro's regime, but also ensures that it does not fall due to internal pressure.

However, Maduro and his government are also playing at being a superpower and interfering in the affairs of neighboring countries. As Hugo Carvajal, former head of the military intelligence service DGCIM, recently admitted, the Venezuelan government has for years used the state-owned company PDVSA to finance left-wing parties and movements in South America—and in some cases in Europe.

Former Argentine President Néstor Kirchner and his wife Cristina, Brazil's Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Gustavo Petro of Colombia, Bolivia's Evo Morales, Spain's Podemos party, and Italy's Five Star Movement have all been recipients of oil (and apparently drug) money from Venezuela for an incredible 15 years.

Caracas is also allegedly trying to destabilize the American empire, for which it is said to be using domestic drug cartels. Groups such as the Cartel de los Soles and Tren de Aragua were classified by Trump in January as "narco-terrorist" organizations, taking hostility towards Venezuela to a new level.

Following in the footsteps of his Republican predecessors – notably Richard Nixon, whose administration brought Augusto Pinochet to power in Chile – he also authorized the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to intervene in Venezuela and reportedly toyed with the idea of a ground invasion of the South American country.

In early November, Trump rejected speculation about the invasion, although he added that "Maduro's days are numbered." In August, he increased the reward for his capture to $50 million.

Carvajal told US anti-drug investigators from the DEA that the cartels, in cooperation with the DGCIM (military) and SEBIN (civilian) secret services, smuggled millions of tons of cocaine into North America. This is likely a source of illegal income for the government in Caracas, which the Trump administration has assessed as a "threat to US interests."

By the end of October, 15 vessels and at least 61 people, whom the US claims were cartel members or affiliated smugglers, had fallen victim to preventive actions. Representatives of the hostile powers were supposed to meet in December at the Summit of the Americas, but it has been postponed indefinitely until 2025 – although one of the reasons was Hurricane Melissa, which meteorologists say is more destructive than Katrina (2005).

The US approach to its South American counterparts clearly shows how differently it treats leaders it considers allies and those who "resist" in any aspect of international relations. Trump has so far rejected invasion as an option, but that may change.

The very fact that someone in the White House leaked this information to the media means that a certain part of the administration—either "permanent Washington" as a whole or careerists in the Pentagon—is preparing for this possibility.