For decades, the United States has been not only Europe's main partner in armaments, but also a major centre for research and development of advanced weapon systems. Now, with Readiness 2030, Europe is not only increasing its defence spending, but also prioritising European defence contractors.

On the one hand, this can boost productivity growth in Europe and create many new jobs in the defence industry. On the other hand, however, this large fiscal stimulus may crowd out private investment, a common problem with government investment programmes.

A study this year by Juan Antolin-Diaz and Paolo Suric managed to compile a comprehensive set of data on 125 years of government defence spending and its impact on the US economy, allowing them to assess the very long-term impact of such an increase in government spending on defence and, in particular, on defence research and development.

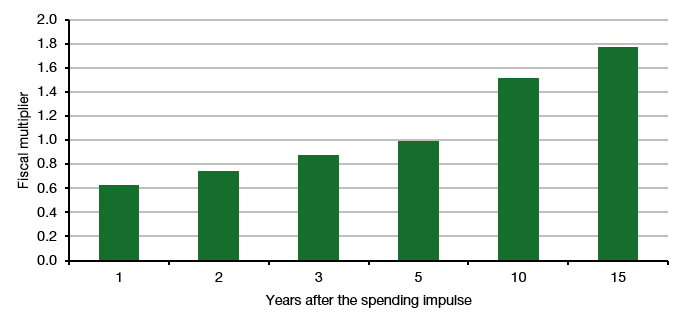

The most important finding is that the fiscal multiplier is greater than one in the long run, meaning that every dollar spent on defense increases the size of the economy by more than one dollar.

Most conventional studies estimate that the fiscal multiplier for U.S. defense spending is about 0.5, with some studies reporting multipliers as high as 1.0. However, this new study shows that the fiscal multiplier continues to increase over time, reaching 1.77 after 15 years. Investment in defence is a long-term investment, which yields results only after 5 or 10 years or even later.

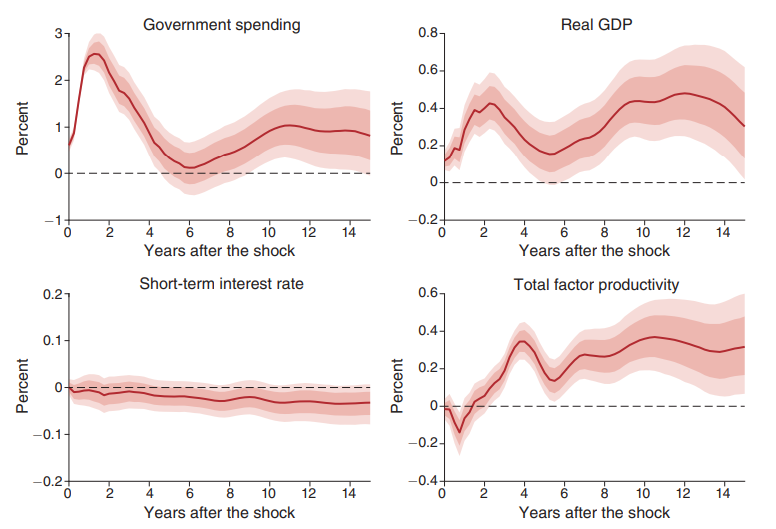

Interestingly, the benefits of increased defense spending come in two waves. The chart below in the upper left corner shows simulated increases in US defense spending.

The chart in the upper right corner shows the increase in real GDP growth. The initial increase in GDP is driven by the increase in defense spending, which is mainly due to the government buying more equipment and hiring more soldiers.

However, after about 8 to 10 years, a second increase occurs. The graph in the bottom right-hand corner shows that this is mainly due to an increase in productivity. This increase in productivity is the result of increased spending on defence research and development. Although this is usually only a fraction of defence spending, it significantly boosts productivity growth in the defence sector and is subsequently passed on to the overall economy.

The main problem with these fiscal spending programs is that they can crowd out private investment because if the government spends more, it usually has to borrow more (or tax more), which leads to an increase in the cost of capital for everyone and thus a decrease in private investment.

The charts above show that this is true in the short term for the first two years after the government increases defence spending. Crucially, however, after eight quarters, private investment and consumption start to pick up, and productivity increases in the long run.

This is also due to the fact that increased government R&D spending "crowds out" private R&D spending and thus contributes to productivity gains in the broader private sector, not just in the defence industry.

The catch is that these studies and graphs apply to the United States.

The question remains whether we have a sufficiently developed innovation ecosystem in Europe to capture the secondary potential of defence investment, as in the US.