After super-cheap nuclear-hydro-wind Sweden, France has the lowest electricity prices in the EU. The main reason for this is the fleet of 57 nuclear reactors in 18 power stations, resulting in a record 68% share of nuclear power in electricity generation.

There is no need to immediately squeal with envy. State-owned operator Électricité de France (EDF) recently went through a thorny road when it booked a loss of 18 billion euros in 2022 and taxpayers had to come running to the rescue with their ten billion.

Although the company has since returned to profits, a fresh audit from September this year states that EDF will need €460 billion of capital investment by 2040 for new projects and maintenance of existing ones. This is not a small amount for revenues in excess of €100 billion a year. However, this is only a marginal figure.

After 15 years, the current mechanism is coming to an end

In this article, I want to address an interesting milestone. This year, the ARENH (Accès Régulé à l'Électricité Nucléaire Historique) mechanism will come to an end. It was created in 2011 to allow competing electricity suppliers to share in the state's nuclear pie and to reduce EDF's quasi-monopoly position.

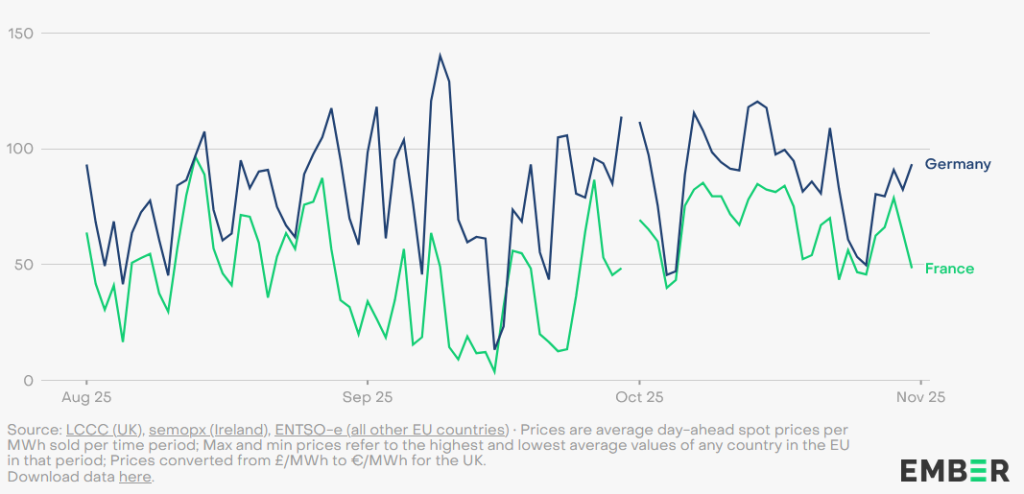

The company had to allocate 100 TWh (roughly 28 per cent of annual production) to the ARENH mechanism each year and offer this electricity to interested parties at a state-set price of €42 per MWh. By comparison, the market price per MWh in longer contracts has been around €100 in Slovakia for the last two years, and €40 to €80 in France.

Until the beginning of 2019, other suppliers had lukewarm interest in this service. However, the market for alternative electricity suppliers has continuously grown, while the rising price of oil and emission permits signalled a future increase in electricity prices. This eventually did not materialise for another three years due to the pandemic, but the high demand for electricity from the ARENH mechanism (40 to 50 per cent more than the allocated capacity) remained.

In February this year, it was confirmed that ARENH would end as originally planned after 15 years, i.e. on 1 January 2026. Given the rise in wholesale electricity prices, selling almost a third of its generation below cost was already hurting EDF badly.

However, Électricité de France will not have "free" electricity sales even after the new year. This is because a progressive "tax on the use of nuclear fuel" is being introduced. This will be levied by the state when EDF's revenues exceed a certain threshold, defined by the cost of production. The exact band will be determined by the budget.

The production costs are set at around EUR 60 per MWh, with the first band of the 50 % tax starting at between EUR 65 and EUR 85 per MWh, followed by a second band of 90 %. Their exact definition will be agreed between the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Energy for three years at a time.

EDF will thus be able to keep 100 per cent of a small part of the revenue above production costs, 50 per cent of another part and only 10 per cent of the remainder. The income from this tax will be used as a rebate on the final electricity prices for consumers.

The government will be balancing between a strict banding that will comfort consumers and a looser banding that would allow EDF to better finance the aforementioned capital needs. For the time being, however, this dilemma is irrelevant, as wholesale prices for long baseload electricity contracts in the country have been below the official cost floor in recent months.

The original methodology for calculating the cost threshold set it as high as €67, but The revision of the methodology reduced it to the aforementioned €60. This shows that there is room for manoeuvre. For example, EDF wanted to include interest costs in the formula, but this was ultimately rejected by the regulator.

Fuel costs are estimated at eight euros per MWh, personnel costs at 10 euros per MWh. Fixed costs are also included in the formula, in particular depreciation at 12 euros per MWh, so that the resulting marginal amount also depends on the amount of electricity produced. More significant outages would imply a different value for production costs. In short, this is a rather demanding exercise with tables and formulas. Even in October, some of the mechanisms and parameters were still not entirely clear.

The offer of long-term contracts

At the same time, EDF is coming to the market with an offer of long-term (10 to 15 years) CAPN contracts [these are contracts designed to make nuclear electricity from a large generator fairly and transparently distributed and available to other suppliers on the market, ed. note].

Originally intended to be for the energy-intensive industry only, they will eventually be available to all customers with consumption above seven GWh per year, but with a total annual cap on sales of 10 TWh per year out of an annual production of roughly 360 TWh, i.e. less than three per cent.

The first contracts with the chemical, cement and even IT (data centres) industries have already been concluded, although the demand is not so massive due to the current low prices on current contracts. The logic of CAPN is risk sharing - industry avoids electricity price fluctuations in exchange for long-term co-financing of nuclear operations.

The demise of the ARENH mechanism first triggered a consumer some concern. A rise in the end price of eight to ten euros per MWh was expected. However, the fall in prices at the end of the year gradually extinguished them.

The large share of nuclear in French generation creates a unique market and regulatory environment. The significant volume of electricity produced with low variable costs - moreover in a state-owned utility - attracts redistribution and regulatory downward pressure on the price.

However, it is clear to anyone with a sober view of the future that the maintenance of the nuclear fleet requires huge capital expenditures that should not be put off. So the French have to balance their regulatory mechanisms intricately under political pressure. Looking at their eastern neighbour, however, they can rather boast about their energy policy.