Currently, Spain has an estimated economic growth of 2.9 percent for 2025, making it one of the fastest growing advanced economies. France, with growth of 0.7 per cent, and Germany, now in its third year on the brink of recession, with a current growth rate of 0.2 per cent, can be quietly envied.

Interestingly, Spain is now in its second year of a budget proviso. For 2024 and 2025, the government has failed to pass a budget, so they have rolled over the 2023 budget. What is the catch of the Spanish economy?

Spain emerged from the fiscal crisis of 15 years ago as an economy of many contradictions. On the one hand, decent growth, on the other hand, still high unemployment in excess of 10 per cent, which has been rising slightly in recent months.

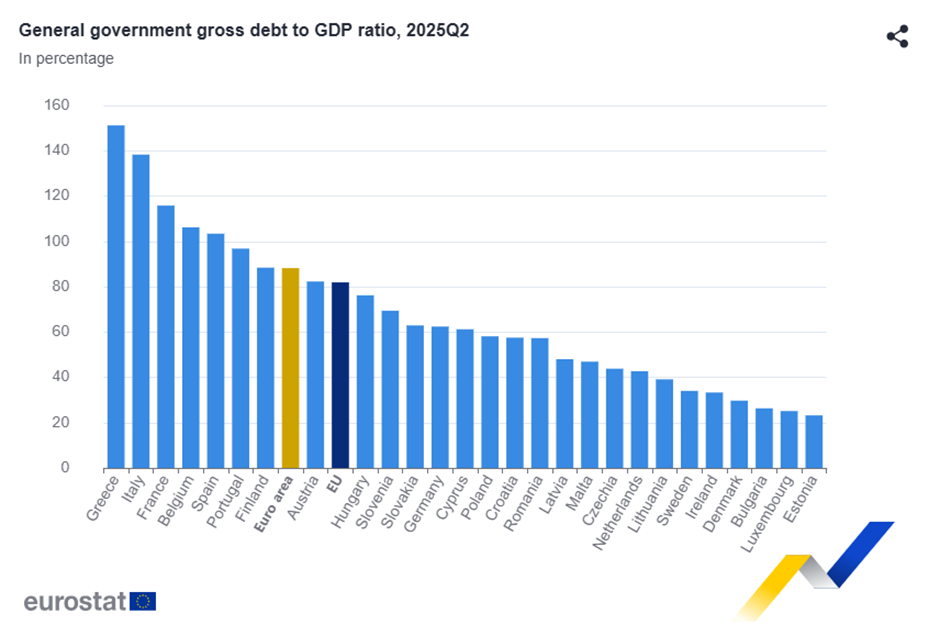

Low energy prices thanks to a large share of renewables and poor networking with the rest of the continent, on the other hand a disastrous blackout. The current budget deficit (-2.6 per cent) is on a par with the euro area average and has fallen for the fifth consecutive year. But public debt stands at 103 per cent of GDP, making Spain the fifth most indebted country in the Union. At the same time, in 2008, it had a debt of only 36 per cent of GDP. At the same time, it should also be added that in 2021 it was up to 116 per cent.

Spain is facing a demographic crisis with the recruitment of immigrants, especially from linguistically related South America. Up to two-thirds of new hires from 2019 to 2024 are foreigners. But again, there is a counter-view, with the argument that the unemployment rate for people under 25 is the second highest in Europe after Estonia, at 24 per cent.

At the same time, the high inflow of immigrants helps to explain the decent growth in Spain's overall GDP. On a per capita basis, growth is still solid, but the lead over other countries is not so clear.

Spain not only dominates European tourism with 85 million visits (second only to Italy with 57 million), but with almost two million units produced, it is the second largest car manufacturer on the continent after Germany.

While in the EU, labour costs rose by an average of 55 per cent between 2008 and 2024 (164 per cent in Slovakia), in Spain they rose by only 31 per cent. On the bright side, this means that Spanish companies have faced less cost growth, while on the dark side it means that real incomes of Spaniards have grown only very slowly since the financial crisis.

Mention should also be made of the classic skeleton in many a European economic cupboard - ECB intervention. Since the 2009 crisis, Spain has been on the receiving end of both explicit and implicit aid from the EU and, in particular, the Eurosystem's central bank.

During the crisis, the Spanish banking sector received a credit line of around EUR 100 billion. Around EUR 40 billion has been disbursed in real terms, of which Spain has so far repaid three quarters. However, Spanish governments continue to benefit from the ECB's purchases of sovereign bonds to prevent a sharp rise in interest rates on Spanish debt.

This was particularly evident in July 2022, when the ECB temporarily sharply increased its purchases of Spanish and Italian bonds to prevent a market panic during the "summer of inflation". According to academic estimates the ECB's quantitative easing saved Spain between €78 billion and €131 billion between 2015 and 2022.

Although Spain's finance minister for the Socialist Party on the IMF website loudly pats themselves on the back and writes about the success they have achieved by "not resorting to belt-tightening" and "creating a safety net for the people", but makes no mention of how Spain's public finances are hanging by a rubber band from the ECB.

A rubber band, the price of which, through the erosion of the euro and increased inflation, we are also paying. Although, looking at Slovakia's public finances, there is no need to jump up and down too much. Slovakia could very easily find itself in the ECB's safety net.