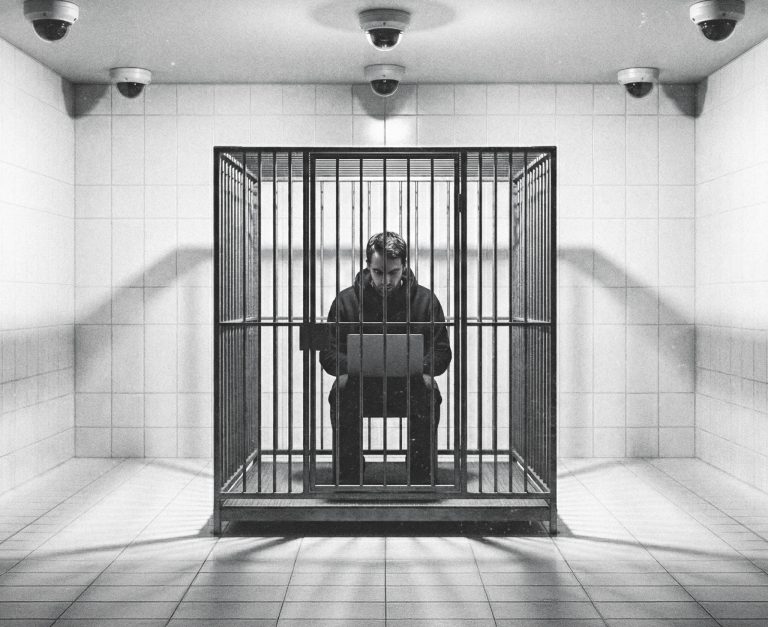

In the past, the Council of the EU prepared a draft regulation under the working title Chat Control, which sought to establish rules for preventing and combating child sexual abuse. With this in mind, the EU wanted to control the content of all messages before they were sent and assess whether they were "okay."

There would be no privacy for EU citizens when exchanging electronic messages (even encrypted ones), as the regulation required providers of such services to check every message before it was sent and assess whether it was problematic in terms of child sexual abuse and the dissemination of such content (CSAM).

Everyone would be subject to blanket monitoring, except for selected groups such as EU employees.

Due to serious concerns about the loss of privacy and unacceptable interference with the fundamental rights of citizens, the proposed legislation did not pass in the form of mandatory monitoring, but a watered-down version is expected to be approved.

Agreement among states on a softer proposal

The Council of the EU has reached a position on the proposed legislation, stating that blanket monitoring will be "voluntary" rather than mandatory on the part of technology companies. The states reached agreement on this compromise after the Danish Presidency of the Council persuaded Germany, which had originally been opposed, and the softened regulation was adopted by a qualified majority.

The proposal was discussed at a meeting of the Coreper (Committee of Permanent Representatives of the Governments of the Member States to the European Union), with the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, and the Netherlands voting against it and Italy abstaining.

The legislative proposal will now move on to the next stage, namely negotiations between the Council of the European Union, the European Commission, and the European Parliament. The final form of the legally binding regulation may therefore change significantly.

The European Parliament has already rejected proposals for blanket surveillance under this proposal in the past, and further negotiations will begin in January 2026.

With the adopted proposal, the Council is repealing mandatory orders to detect inappropriate content and has instead decided to shift the burden of responsibility to technology platforms by requiring them to take mitigating measures against the spread of prohibited content.

Platforms will decide for themselves on blanket monitoring

Under the new rules, online service providers will be required to assess the risk that their services could be misused to spread material depicting child sexual abuse.

Based on this assessment, companies will have to put in place mitigating measures to combat this risk. Such measures could include making tools available to users to report child sexual abuse online, controlling what content is shared with others, and implementing default privacy settings for children.

In addition, the relevant national authorities will still have the power to oblige companies to remove and block access to content or, in the case of search engines, to remove search results. The regulation also establishes a new EU agency, the EU Center for the Prevention and Combating of Child Sexual Abuse, which will support Member States and online providers in implementing the law.

One of the key and criticized mitigating measures will be the "voluntary" monitoring of all messages by companies, which will most significantly reduce the risk of exposure to fines or other sanctions by the Union.

In practice, this means that the Council has shifted the responsibility for monitoring from its shoulders to those of technology companies under the threat of heavy fines.

Consent to monitoring will be provided by the user

Currently, many experts have expressed their concerns that companies will decide to incorporate "voluntary monitoring" into their services on a permanent basis, thereby easily removing their degree of responsibility for inappropriate content.

They would achieve this by simply adding user consent to the terms and conditions of use of their product, whereby a person would traditionally "voluntarily agree to the monitoring of all messages" without reading the terms and conditions, otherwise they would not be able to use the service.

From the perspective of compliance with the rules by technology companies, this would be the easiest way to comply with the proposed rules, but this does not, of course, preclude the introduction of their own internal risk assessment system and thus the "switching on or off of blanket monitoring."

However, even "voluntary" blanket monitoring is problematic from the perspective of EU law. According to the EU Charter, every citizen of the Union has the right to respect for private and family life, home and communications, and the right to the protection of personal data (the management of which must be subject to legality, purpose limitation, proportionality, and independent supervision).

EU case law prohibits unjustified blanket surveillance

The case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union on blanket surveillance of citizens clearly prohibits such practices.

The decision of the Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice of the European Union in the Digital Rights Ireland case (C-293/12 and C-594/12) found the directive to be invalid. The directive required providers of publicly available electronic communications services (telephone operators, internet providers) to retain communication data (so-called traffic and location data, metadata) of all their customers for a minimum of six and a maximum of 24 months for the purpose of combating serious crime.

The Court found that the directive constituted an overly broad and serious interference with privacy and the right to protection of personal data. It imposed a blanket obligation to collect data from the entire population, regardless of whether there was any suspicion of criminal activity, and did not provide sufficient safeguards to protect data from misuse.

This practice was also confirmed by the Grand Chamber of the CJEU in its decision in joined cases C-511/18, C-512/18, and C-520/18 (known as La Quadrature du Net). In this case, the court also ruled against the blanket and indiscriminate retention of data.

From a legal perspective, it is irrelevant whether such mass surveillance and data collection is a legal obligation or a "voluntary" option for companies to avoid fines. What matters is whether such interference is necessary, proportionate, and subject to effective supervision so that citizens' rights are not unduly restricted.

Too much sensitive data to track

Companies could formally argue that the user voluntarily agrees to the terms of service, which include scanning, so everything is fine. However, under the GDPR, such consent must be free, specific, informed, and unambiguous, and cannot simply be hidden behind an "I agree" option, otherwise the service cannot be used.

In the case of large platforms (WhatsApp, Messenger, etc.), which are essential for social and work communication in practice, the "I disagree" option is purely theoretical. This obligation will apply to all large platforms, so users have no real option to use modern communication channels without accepting mass monitoring.

Monitoring private messages, including intimate photos, health data, political opinions, and the like, not only creates the risk of processing special categories of personal data without the necessary consent or justification, but also constitutes an absolutely unacceptable invasion of an individual's privacy. The right to privacy will essentially cease to exist, which is also incompatible with European values.

Artificial intelligence will make mistakes

The technological implementation of blanket surveillance itself is to be based on artificial intelligence (AI). It is natural that such massive amounts of data cannot be processed effectively by real people.

However, this opens up another serious problem, namely the error rate of AI. The risk of innocent people being flagged as suspects of serious sex crimes (and subsequently reported to state authorities) will be extremely high. Technical experts warn of cases of so-called false positives, where, for example, an innocent picture from a family vacation would be flagged as illegal.

Providers may be motivated to scan more aggressively to show that they are "responsible" and "proactive," increasing the risk of false positives and subsequent interference in the lives of innocent people (police reports, account blocking, stigmatization).

Sensitive data and conversations, which will include, for example, medical facts or other medical content, will also be checked by unknown persons in the new agency, which is legally unacceptable.

There are countless possible scenarios for abuse of the system, unjustified interference with individuals' rights, and clearly illegal actions resulting from the regulation. The areas of political rights or employment, where the confidentiality of communications is crucial – such as in the case of journalists – but also other sensitive authorities in the Member States will be subject to surveillance by European officials.

All these areas present endless possibilities for the surveillance of communications to result in clear violations of individual rights.

A private company will decide on citizens' rights

At present, it is unclear who will decide whether or not blanket surveillance is necessary, and how. It is outrageous that this will be decided by private individuals in companies, rather than by state authorities.

The details of the cooperation between the new European agency and private technology companies, the qualifications of these people, and so on are also unclear. It is also unknown how the agency's employees will cooperate with the state authorities of the countries in which the criminal activity takes place and what powers they will have to do so.

It is also questionable how people will be able to defend themselves against the misuse of their own private information by private companies whose primary goal is to make a profit.

Will they then assert their rights in national courts or in European courts? And who will actually be responsible? The company that complies with the regulation, or the Union that issued the regulation?

The fight against child sexual abuse is a top priority in every society, but even in its "voluntary" form, the proposal does not change much from the original mandatory monitoring of all citizens (except for selected groups such as EU employees).

The proposal did not present any vision of how it actually intends to prevent abuse effectively (the idea of prosecuting millions of crimes of this type annually across the EU, often transnational, is a pure illusion), but there are too many unknowns to subordinate a generally acceptable thesis (the protection of children) to an absolutely unacceptable legal regulation.

Theoretical voluntariness on the part of technology companies means that blanket surveillance may be introduced. And if such a measure is not permissible on the part of state authorities or EU institutions, it is absolutely out of the question for it to be transferred to private companies.