Gradually, central banks have thus become by far the largest holders of sovereign debt. The bursting of the bond bubble therefore hurt them the most.

If we look specifically at the US central bank, it is technically insolvent even formally.

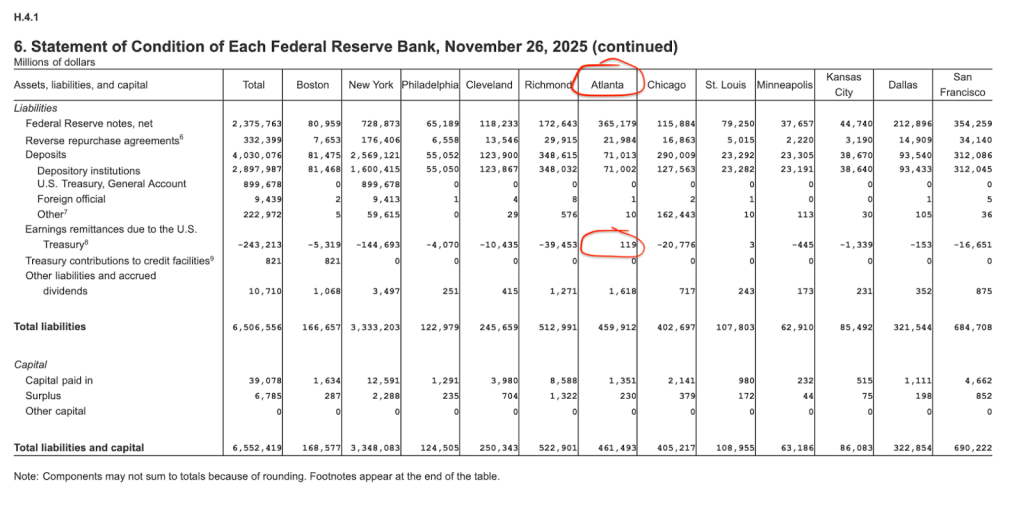

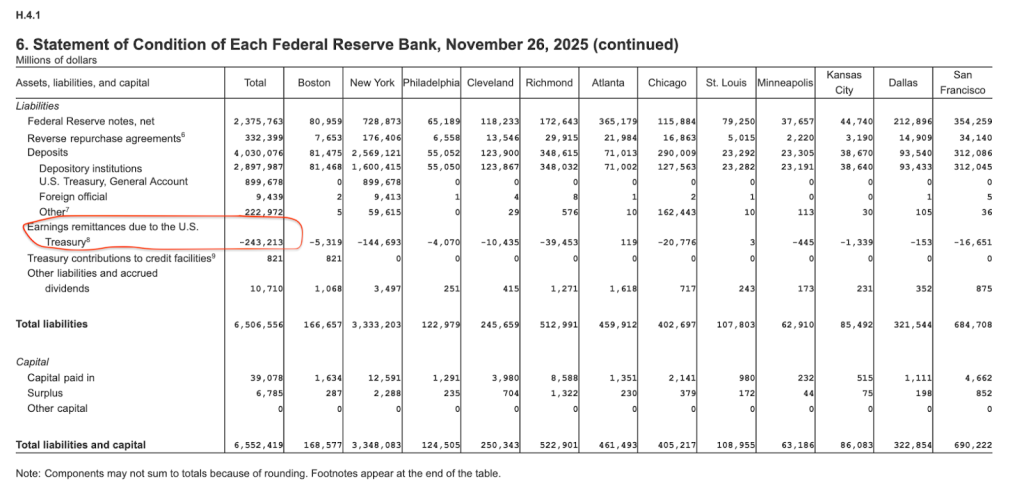

The US Federal Reserve (Fed) is made up of twelve regional banks which, with the bursting of the bond bubble and the skyrocketing of interest rates, began to generate huge ongoing losses in the autumn of 2022. In fact, in the US, during the financial crisis, in an attempt to create a floor on market interest rates, the Fed made it compulsory for commercial banks to pay interest on the reserves they hold at the central bank. These have become significantly more expensive as interest rates have risen.

Of the individual branches, the Fed's Boston, New York and San Francisco branches, which hold the most of these commercial bank reserves, are particularly noteworthy. In contrast, profits are still generated by the Atlanta or St. Louis Fed branches. This is because the Atlanta Fed, for example, has relatively more cash on which it does not have to pay interest to banks.

This is because it also includes a branch in Miami with a huge demand for cash. In fact, its physical dollars are largely used to finance the drug trade south of the US border. Drugs help keep the state central bank in the black.

Not enough. The cumulative realized losses of the Fed's various branches, after accounting for profits, already exceed $243 billion.

That's $197 billion more than their official equity. Since state central banks habitually pay profits to the U.S. Treasury, the Fed reports this accumulated loss as a liability to be paid to the Treasury, albeit with a negative sign. The US Fed is thus technically insolvent today, even before accounting for unrealised losses on bond holdings. These amount to another approximately 1 060 billion dollars.

Table, shake it off

The central bank, which has a state-guaranteed monopoly on money, doesn't have to worry so hard about technical insolvency. It is the economic equivalent of a stool to wipe the slate clean, and the additional capital can simply be printed or made up by simply entering it into a database. As I wrote in my book Bad Money:

"Positive equity capital is not a prerequisite for an efficient central bank. It is a marketing tool of the state monopoly money producer that helps convince currency users that the central bank is behaving relatively responsibly.

The central bank has the ability to continuously pay off its liabilities by creating other liabilities. For example, if it has a liability on the liabilities side in the form of its governor's monthly salary, all it needs to do to cover it is to create another liability, i.e. new banknotes or an entry in the reserve account of a commercial bank where the governor has a personal account.

Technically speaking, the central bank can create as much equity as it wants. All it has to do is print new money and buy government bonds with it. The state can then 'invest' the funds thus raised to increase the central bank's equity."

The Slovak experience

We have experience of negative central bank equity ourselves:

"The Slovak national central bank, which is part of the Eurosystem, has been operating with negative equity for almost a decade[Bad Money came out in 2015, author's note]. After the stabilisation of the Slovak economy at the turn of the millennium and the appreciation of the Slovak koruna, the bank incurred high losses from holding foreign exchange reserves. NBS closed 2011 with equity of minus EUR 4.5 billion. Despite this, the central bank is still functioning, conducting a common monetary policy, subsidising interest on loans for its employees, paying the salaries of officials and economists."

Transfers from the budget

Monetising its own losses, however, does not look good and reveals too much about how the "sausage of bad money" is made today. Central banks in developed countries therefore tend to recapitalise with a transfer from the state budget when someone starts digging into that formal capital hole. The European Central Bank has already been recapitalised:

"Despite a short history of only one decade, its equity capital has already been increased once. The decision to raise it from €5.76 billion to €10.76 billion was taken in December 2010 out of concern that market fluctuations linked to the euro crisis could threaten its paper solvency."

Today, transfers from the state budget back to the central bank are already being made in the UK. It is estimated that it will cost them a total of £130 billion over the next five years.

The unrealised losses of the Bank of Japan, which holds government bonds worth one year's gross domestic product, were already at 28.6 trillion yen in March 2025, about five per cent of the country's GDP. Given the further alarming rise in interest rates on government bonds there, it will be considerably more today.

Economically, those unrealized losses by the Fed (and other central banks) are already being translated into dollar (and other currency) strength. This manifests itself in its weakening against equities, bitcoin or other currencies. The losses have reduced the ability of this central bank to create new money in the future without it being reflected in an immediate rise in prices.

A technically insolvent Fed with large unrealized losses and huge losses in the other major sovereign central banks of the world are one of the key factors behind the record rise in the price of gold in recent years.