The American intervention in Venezuela raises many questions. The White House's justification is unconvincing. Most of the hypotheses circulating about Donald Trump's motives also have certain flaws. Even more surprising, however, is his appetite for the world's largest island.

Certainly, Greenland is extremely rich in mineral resources. In addition to graphite, copper, nickel, gold, and titanium, the island offers reserves of oil and natural gas, as well as uranium. The most important are rare earth metals, including those with key uses— neodymium and praseodymium (for the production of super-strong magnets for wind turbines and electric car batteries), dysprosium and terbium (used as additives to make magnets resistant to high temperatures), yttrium (lasers, superconductors) and scandium (aerospace industry).

The size of their reserves is somewhat of a mystery. Although estimates suggest tens of millions of tons, the economically viable volume of rare earths is around 1.5 million (eighth place in the world ranking). However, less than 20 percent of the island's area is covered by permanent ice, which means that there is considerable scope for further discoveries.

The United States' interest in the island is therefore understandable. Especially since they lag far behind China in the mining and processing of rare earths. If they want to remain an independent military and economic superpower in the coming decades, they need to step up their efforts in this field. But starting mining in Greenland is more challenging than building a business on a greenfield site.

Almost nothing is mined in Greenland. There are reasons for this.

Despite its rich reserves, almost nothing is mined on the world's largest island today. The exceptions are two small mines for gold (Nalunaq) andanorthosite (White Mountain). In the long term, they are one of the main reasons for the local population's concerns about environmental disruption.

This is partly because various chemicals are used to separate the minerals, but another problem is that several rare earth deposits also contain radioactive uranium.

Of course, if Trump were to bring Greenland under US control, environmental concerns would take a back seat. However, regulations and the concerns of Greenlanders are not the only things holding back the development of mining. The main problems are underdeveloped infrastructure and harsh climatic conditions.

The southern part of the island is the most developed, and it is also where the largest and most promising rare earth deposits are located.

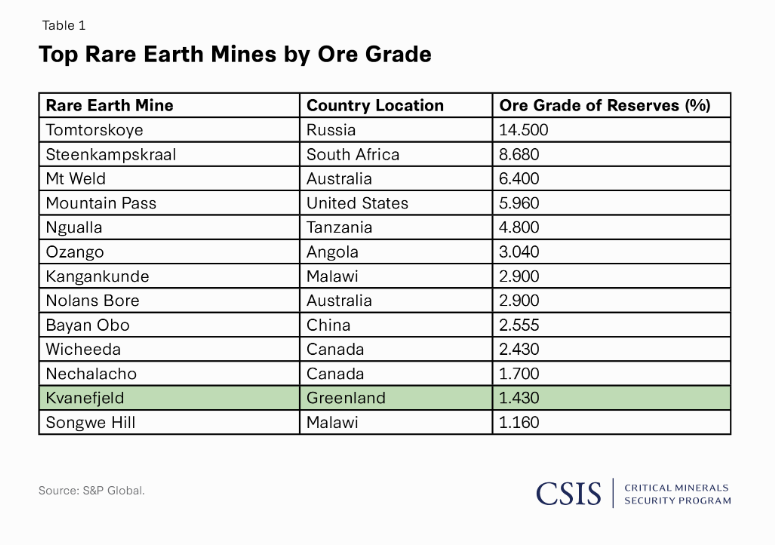

Kvanefjeld is the third largest known deposit in the world, withtotal reserves of 11 million tons. It is an attractive site mainly due to the high content of rare earth elements in the ore – around 1.43 percent. The area also contains around 270,000 tons of uranium.

The nearby Tanbreez deposit is potentially the largest in the world, with estimates of up to 28 million tons of rare earth elements. Although the ore there is poorer (0.38 percent), the site is still attractive as more than a quarter of the reserves are heavy rare earth elements.

However, even in the inhabited south, where both sites are located, there are no adequate roads (according to data from 2022, there were approximately 150 kilometers) or railways for standard mining project logistics.

At the same time, it would be necessary to bring in large numbers of skilled workers, who would need to be provided with accommodation, food, and a basic standard of living. Electricity supplies and the size and number of ports are also bottlenecks.

The mining problem is followed by the question of where the mined ore will be processed. If Washington does not want this to happen in China, it has two options: either build new factories in Greenland or import the mined ore to the United States at great expense.

However, the two processing centers there (Mountain Pass and White Mesa Mill) would also have to significantly expand their capacity, as the US has historically processed ore from the Mountain Pass deposit in China, and the turnaround has only occurred in recent years. It should not be forgotten that 99 percent of the imported ore would essentially be unwanted waste.

The economic viability of extracting rare earths from Greenland, and especially the time frame, are simply uncertain. Before they see the light of day, they will require huge investments and easily more than a decade.

Why Trump wants Greenland after Venezuela

Analysts at the Center for Strategic Studies assess that although Greenland's mines represent "a potential path to improving US access to rare earths, realizing this potential requires more than just funding," namely "a long-term commitment to infrastructure, genuine community engagement, and diplomatic coordination."

Given this, it is questionable whether the entire journey for Greenland's wealth is worth Trump starting a conflict with his closest allies. The hypothesis about the strategic importance of the island, which he himself communicates, seems more promising.

Currently, the sea routes connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in the north are only navigable in summer, but melting glaciers are extending this period. This shortens the distance between Asia and Europe by 7,000 kilometers compared to the route through the Panama Canal. The research and consulting group Wood Mackenzie writes that from 2022, the average number of ships passing through will double compared to the previous decade.

Strengthening the US military presence around the island and controlling this emerging corridor therefore makes sense.

Nevertheless, the hypothesis about critical raw materials should not be underestimated. Trump's appetite for Greenland may indeed stem from concerns about the monopoly that China has created in the field of strategic raw materials, despite the enormous capital requirements.

Gaining Greenland would not only mean greater reserves for the United States, but also prevent Chinese companies from "colonizing" the island and increasing Beijing's lead in a key industry. One example among many: although the Kvanefjeld project is (mostly) owned by the Australian company Greenland Minerals, the Chinese company Shenghe Resources is its largest shareholder.

This hypothesis would also fit with the events surrounding Venezuela, where the US wants to push in capital from American oil giants to multiply oil production there and return it to historic highs. While in the case of Greenland's wealth, it would be more a matter of US national security, the interest in the South American country would be in energy.

Oil production in the US is peaking and isexpected to start declining by the end of this decade. Oil from Venezuela could thus (if the major players decide to undertake a significant overhaul of the country's neglected infrastructure) replace it for a certain period of time and stabilize the US's position as an energy superpower.