At least from the perspective of the stock markets, European countries are currently benefiting from a more cautious, cool-headed approach to Trump's often harsh tariff rhetoric, which he often subsequently softens with his actions. Financiers and investors, not only on Wall Street, have even coined a special term for this phenomenon, TACO [explained in more detail below, editor's note], which they use, for example, when trading stocks.

As was the case last year, European countries should keep a cool head and not escalate the conflict with Trump over the tariffs he is threatening to impose in an effort to acquire Greenland. It is necessary to wait and see how the US stock markets react on Tuesday (there was no trading in the US on Monday). It is also necessary to monitor whether Trump's tariffs will be invalidated in the coming days by the US Supreme Court, which could issue its verdict on the matter this week. Finally, we must wait and see whether Trump will "eat his words" and back down from the tariffs, as he did several times last year.

The answer to the first question was that US stocks opened Tuesday's trading on Wall Street with a sharp decline in response to President Trump's threats to impose new import tariffs on some European countries. Analysts said the reason was concern that the threat of new tariffs would lead to retaliatory measures by the EU, which could mark the beginning of a new trade war.

European stocks performed better

European stocks included in the key Stoxx Europe 600 index have appreciated more than five times as much as US stocks included in the Standard & Poor's 500 index since Trump's inauguration last year. From January 21, 2025, the first day after the inauguration, to last Friday, European stocks in euros gained 17.3 percent, while US stocks in the same currency gained only 3.3 percent.

Even this week, it is unlikely that Trump's new "Greenland" tariffs on eight European countries, NATO member states, will cause European stocks to weaken significantly. Moreover, the gap between European and US stocks has widened since the end of last year. European stocks thus have a sufficient cushion for a possible decline, which, if it occurs at all, should only be temporary. There are several reasons for this.

Four main reasons

First, Trump may not ultimately impose his tariffs, as he has "backed down" several times in the past. In fact, as we mentioned earlier, the term TACO has become established for this trait of his behavior, based on an article in the Financial Times last May.

The term TACO is an acronym for Trump Always Chickens Out, which appeared for the first time in the context of tariffs in the aforementioned article. Professional investors on Wall Street have taken a liking to a trading strategy they also call TACO. It simply consists of buying stocks relatively cheaply after Trump threatens tariffs and the market drops, and then selling them again once they rise in price, when Trump "backs down" and withdraws his threat.

Secondly, Trump, as he did many times last year, has given himself time to introduce tariffs until February 1. So he still has about two weeks to act. And that's how much time he has to back down. For example, a few days ago, he announced secondary tariffs on countries that trade with Iran, primarily China, followed by the United Arab Emirates, India, and Turkey. These countries were supposed to see an immediate 25 percent increase in customs duties, Trump announced less than a week ago—but so far, this has not happened.

Thirdly, Trump's tariffs – last year's "reciprocal" and "fentanyl" tariffs, as well as the "Greenland" tariffs – may very soon be invalidated by the US Supreme Court, meaning that the US administration would have to stop applying the first two sets of tariffs and would not be allowed to introduce the third set.

Fourth, the escalating tension over Greenland should be another boon this week, at least for European arms manufacturers and their shares, whose growth would in such a case significantly dampen any decline in the broader European market.

What does this mean?

European leaders should keep a cool head throughout this week. They should not provoke Trump, brandish a digital tax or restrict investments by American companies in the EU, as French President Emmanuel Macron is demanding, wanting the Union to activate its hitherto unused tools against economic pressure for the first time ever.

In fact, they should wait until at least Wednesday. This will allow them to see the reaction of US markets (Trump closely monitors stock market developments) and perhaps even the verdict of the US Supreme Court, and finally, for example, how Trump "eats his own words" and withdraws the threat of tariffs again.

It should also be taken into account that Europe is by far the largest foreign provider of finance to the United States. According to Deutsche Bank's calculations, the old continent owns US stocks and bonds worth eight trillion dollars, almost twice as much as the rest of the world. This is not exactly a "weak card," but rather one of the few strong cards that Europe currently has in its hand. So it has something to play with.

And US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, for example, will tell Trump how significantly the US and Europe are linked in terms of capital. It was probably him who convinced Trump last year, after Liberation Day in April, to take a three-month break from tariffs, when US stocks, bonds, and the dollar plummeted after high tariffs were imposed on almost the entire world.

More favorable exports for countries not burdened by tariffs

For Czech (and Slovak) exporters to the US, Trump's tariffs on Greenland may also be good news, as these countries would face up to four times lower tariffs than their German competitors, for example.

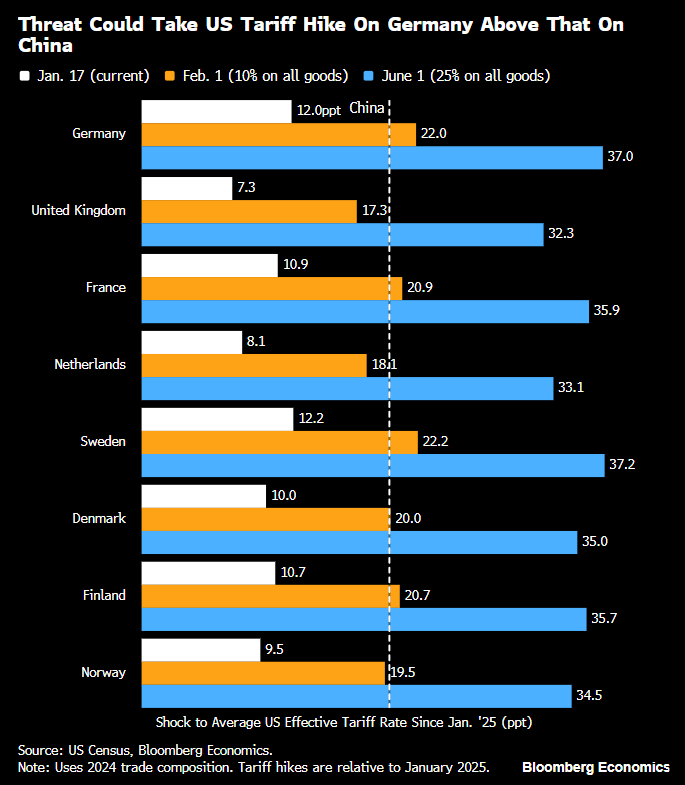

The total increase in tariffs under the Trump administration on imports from Germany and France may already exceed that on imports from China in February.

On Sunday, US President Trump announced a new set of tariffs on eight European countries, NATO members, which this week decided to send several dozen soldiers to Greenland. These countries are Germany, France, Britain, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Norway. Trump plans to introduce the 10% tariffs on February 1 this year and apply them until European countries allow him to buy Greenland outright. He is prepared to increase the tariff to 25% in June.

If Trump follows through on his threat and introduces the new 10% tariff on February 1, it will mean that during his second term in the White House, he has increased tariffs on Germany and France, for example, more significantly than on China. For example, a new 10 percent tariff on German exports to the US would mean that American importers of German goods would pay an average of 22 percentage points more to the US Treasury than in January 2025, just before Trump took office.

Over the past year, Trump has increased tariffs on German imports to the US by an average of 12 percentage points. Now, in an effort to acquire Greenland for the US, he would add another ten percentage points, so that his total increase in tariffs on German imports of 22 percentage points would exceed his increase in tariffs on imports from China, which has accounted for 20 percentage points over the past 12 months or so.

A similar situation would arise for some other countries that have decided to send their troops to Greenland. For example, French exports to the US could face an average tariff increase of 20.9 percentage points during Trump's second term, starting on February 1. The average effective rate takes into account the structure of a country's exports to the US, as well as exemptions that apply to various types of goods exported in this way, as steel and aluminum, for example, have their own sectoral rates.

Trump's new tariffs may, on the contrary, increase the competitiveness on the US market of exporters from those European countries that are not subject to the new tariffs. These include the Czech Republic and Slovakia. From February, they would then face approximately half the tariff on exports to the US as the eight countries mentioned above. Italy and Ireland, which have relatively strong trade links with the US among EU countries and are not subject to the new tariffs, could benefit most from this situation.

An even more significant difference between the tariff rate applied to the eight countries mentioned and that applied to other European countries could arise from June. If the United States does not acquire Greenland by then and Trump actually carries out his threat, tariffs on these eight countries will increase by another 25 percent. For example, Trump's total increase in the tariff rate on imports from Germany would then be 37 percentage points. The tariff on German imports to the US would thus be approximately four times higher than that faced by Czech or Slovak exporters.

However, it remains to be seen whether Trump will actually introduce the new tariffs.

Both texts were originally published on the website lukaskovanda.cz.