Almost thirty years ago, the Czech Republic pressured its national bank to quickly sell its gold, fearing that if it did not do so quickly enough, other central banks would beat it to the punch and it would have no choice but to sell at an even lower price. In the end, however, it sold this precious metal at historically low prices.

Within a few months, the Czech National Bank (ČNB) disposed of gold that had been accumulated since the days of Austria-Hungary, whose central bank at the time had created the basis for the new state's gold reserves by transferring more than a dozen tons of the yellow metal when Czechoslovakia was founded. During the same period, this reserve was expanded with gold from the collection of the newly formed republic's gold treasury, which at the time consisted of voluntary contributions from its citizens.

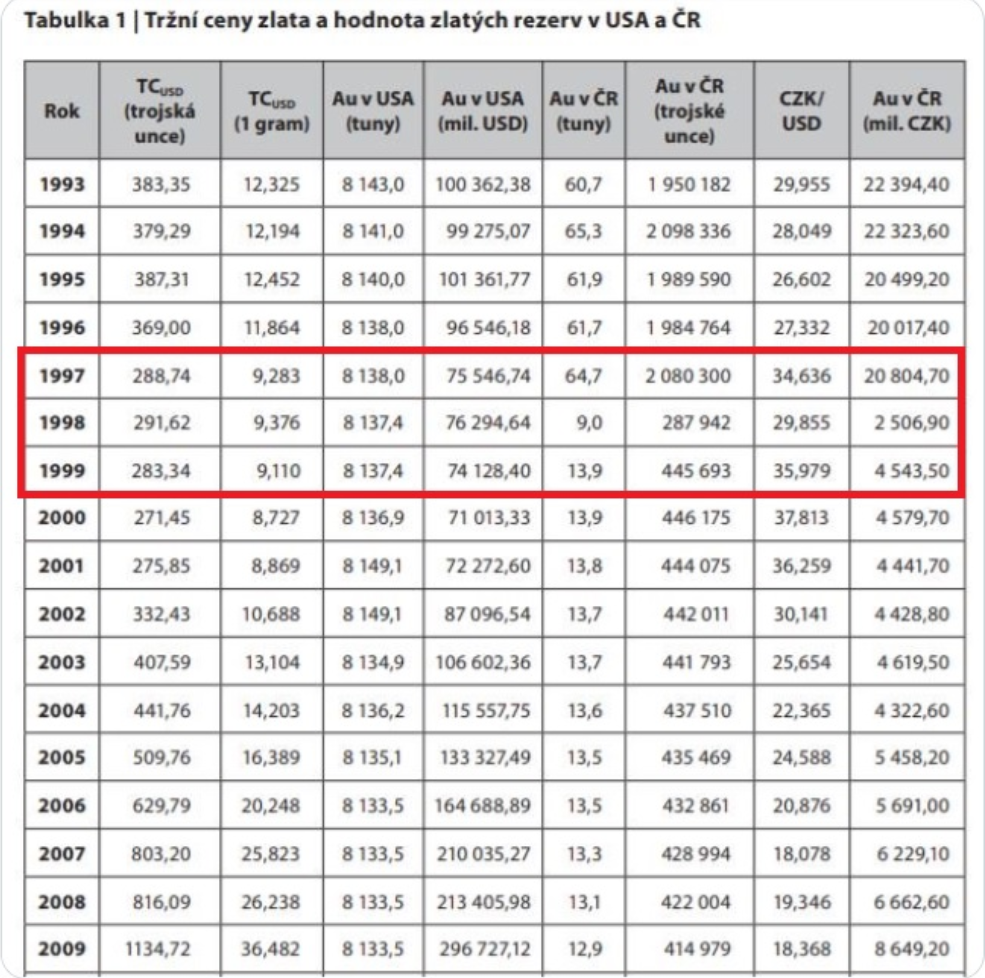

As shown in the published table, the Czech central bank disposed of approximately 51 tons of gold at the end of the 1990s. It earned approximately 16 billion Czech korunas for it, which, due to inflation, corresponds to less than 40 billion korunas (almost 1.65 billion euros) today. If it sold the same amount of gold on the current market, it would earn 170 billion Czech korunas (more than seven billion euros), which in real terms – after taking inflation into account – is about 130 billion korunas more (around 5.35 billion euros).

One specific example illustrates the CNB's urgent need to sell gold at that time. In 1998, the victorious powers of World War II dissolved the Tripartite Commission for the Return of Gold Stolen by the Nazis. As part of the final settlement, the CNB received approximately 330 kilograms of gold from this commission.

It wasted no time and immediately sold it for CZK 100 million, sending almost the entire amount to the state budget. Due to inflation, the 100 million at that time corresponds to roughly 225 million korunas today. However, if the CNB had sold the aforementioned portion of gold looted by the Nazis this year, it would have earned 1.1 billion korunas, which is almost five times as much in real terms.

Back in 2000, CNB representatives argued that the selling price of the metal, which reached $323 per ounce in 1997, was still a success [it has now exceeded $5,000 per ounce, ed.]. However, in terms of the speed with which the country liquidated its gold reserves in the second half of the 1990s, only Malta could compete with the Czech Republic in today's EU.

Other central banks in EU countries acted more sensibly and proceeded more cautiously. From around 2005, gold began to appreciate significantly, bringing a 1,100 percent return to date. And the Czech Republic was left with nothing but tears.

Of course, everyone is a general after the battle. In the geopolitically peaceful era of the late 1990s, no one could have guessed how dramatically gold would rise in price. However, the CNB sold at an extreme pace, even by EU standards. Others avoided such hasty action.

The text was originally published on the website lukaskovanda.cz.