Cubans from all walks of life are struggling to survive, coping with prolonged power outages and soaring food, fuel, and transportation prices, while the US threatens to figuratively "imprison" the communist nation.

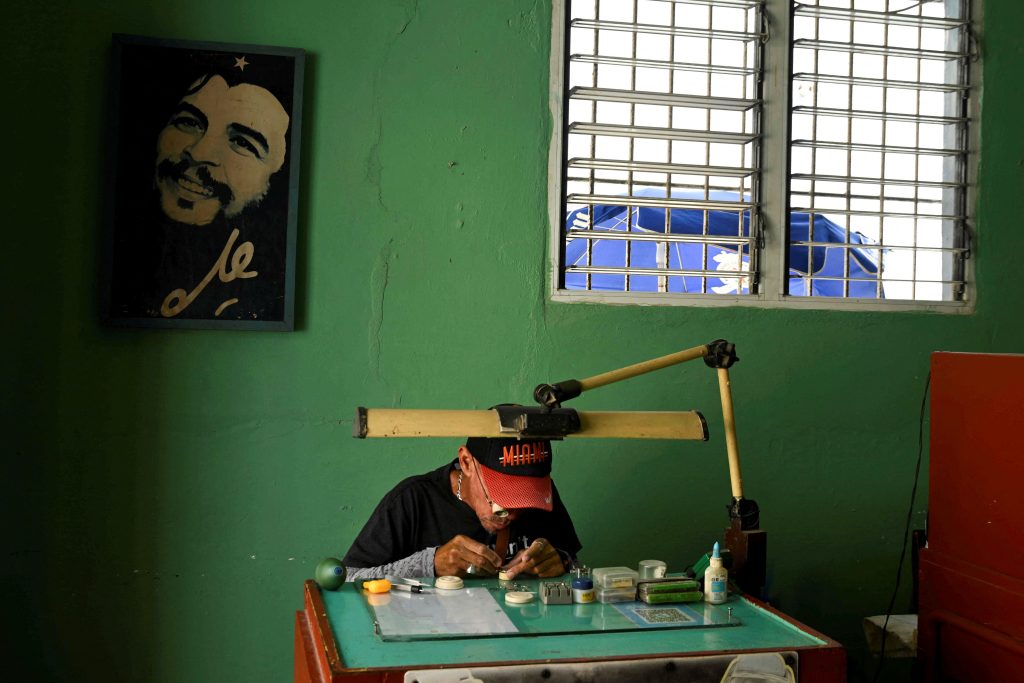

Reuters interviewed more than three dozen residents of cities and neighborhoods around the capital, Havana—the country's political and economic engine—ranging from street vendors to private sector workers, taxi drivers, and government employees.

Discussions with them painted a picture of people pushed to their limits as goods and services—especially those tied to increasingly limited fuel supplies—become scarcer and more expensive.

For most of rural Cuba, this is not an entirely new phenomenon. The island's fragile and outdated power generation system has been slowly failing for years, and residents have grown accustomed to spending hours without functioning electricity, internet, or water pumps.

The economy is going downhill

Even the coastal capital, whose streets are lined with cars from the 1950s and colorful, albeit dilapidated, Spanish colonial architecture, was doing better until recently.

It now appears to be engulfed by economic crisis, as the country is experiencing a fuel shortage after Venezuela and then Mexico stopped oil supplies to the Caribbean island.

US President Donald Trump has announced that tariffs will be imposed on imports from countries that supply Cuba with oil. This move has increased pressure on Washington's long-time enemy following the ousting of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in January – a key Cuban ally.

In many other countries, these conditions would have driven people into the streets, but in a country where dissent has long been suppressed, there were few signs of protest. However, it is unclear how much more Cubans are willing to endure.

The Cuban peso has lost more than a tenth of its value against the dollar in three weeks, pushing up food prices. "It has put me in an impossible situation," says Yaite Verdeci, a Havana resident and housewife. "No salary can cope with this."

Everyday life is becoming increasingly difficult

When Trump was asked about the possibility of US military intervention in Cuba shortly after Maduro's capture, he said he did not think an attack would be necessary because "the regime there is ready to fall on its own."

Last week, Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez declared an "international state of emergency" in response to US warnings about tariffs, which he said posed "an unusual and extraordinary threat."

However, the Cuban government has not specified how it intends to address the growing threat of a humanitarian crisis.

Many of the Cubans interviewed by Reuters said that their daily lives, already difficult enough, had been reduced to meeting basic needs such as securing food, water, and fuel for cooking, and that in recent days it had become noticeably more difficult.

Queues for gasoline have grown significantly in recent days at several gas stations in Havana that are still supplied with fuel. And since the US blocked Venezuelan oil supplies to Cuba in mid-December, virtually all gasoline has been sold at a "premium," i.e., in dollars—a currency that few Cubans have access to.

"You used to be able to register and buy fuel (in pesos) once a month," said Havana resident Jesús Sosa, referring to a mobile app that notifies residents when it is their turn to fill up their cars. "Not anymore. Sales in the national currency have stopped."

Pay up or stay home

The crisis has affected both public and private transport, with some buses and private taxis being taken out of service and others forced to raise their prices.

Daylan Perez, 20, who hails private taxis for clients in Old Havana, said that fewer buses mean people now have no choice but to pay rising fees for private transportation. "You have to pay the price or stay home," he added.

Even electric vehicles—once considered a panacea in a city with fuel shortages—have been affected by power outages, which now last eight to twelve hours or even longer.

Havana taxi driver Alexander Leyet recently switched to an electric three-wheeled taxi, thinking he had outsmarted the others. "Now, because of the power outages, I can only charge my taxi for four or five hours," he said.

The government, which has its roots in Fidel Castro's 1959 Cuban revolution, has survived for decades despite sometimes brutal economic problems, defying regular predictions of imminent collapse or uprising against it.

It has long claimed that these are attempts to incite an uprising led by the United States, but the latest widespread protests took place during the pandemic year of 2021. Between 2019 and 2024, the Cuban economy contracted by 12 percent.

Crackdowns on any form of dissent, combined with the emigration of approximately one million people since the beginning of the pandemic [2024 statistics estimate that 9.75 million people live in Cuba, editor's note], have almost completely eliminated organized opposition in the country. Cubans approached by Reuters generally refused to answer questions about the possibility of protests.

Power outages

However, none of the Cubans interviewed questioned the need for change.

"I just pray that God will find a way to get us out of this (chaos)," said Mirta Trujillo, a 71-year-old street vendor from Guanabacoa, near Havana, who broke down in tears when she told a Reuters reporter that she could hardly afford to buy food anymore.

She used to depend on a government rationing program for basic goods. But after the pandemic, it was gradually phased out as tourism revenues and other sources of hard currency dried up.

"I'm not against my country, (...) but I don't want to die of hunger," she said.

A Reuters reporter also witnessed an accident in the evening at a busy intersection in Havana, where traffic lights were not working due to a power outage.

"Sometimes when the power goes out, accidents happen," said Raysa Lemu, whose apartment overlooks the boulevard in Marianao on the outskirts of Havana. "They used to cut off the power two or three times a week, but now it's every day and sometimes it lasts up to twelve hours."

Julia Anita Cobas, a 69-year-old housewife from Guanabacoa near Havana, gets up every morning at 4 a.m. to make the 16-kilometer journey, which now takes almost four hours (including the return trip). With fewer public transport options available, the journey has become longer and more expensive.

"I leave home before sunrise and I don't know how I'll get back," she said. But Cobas, who was born just before Castro's revolution, said she didn't expect Trump to improve things.

"Since I was born, (the United States) has been threatening us, and we face difficulties every day. But we have survived everything," she said.

Aimee Milanes, a 32-year-old resident of Reparto Electrico near Havana, said that neither the Cuban nor the US government offered her much hope.

"We are drowning. But there is nothing we can do about it," Milanes emphasized. "It's about survival. Nothing else."

(Dave Sherwood, Reuters)