Unemployment in the Czech Republic is at a nine-year high. This year, for the first time since the beginning of 2017, it has exceeded the five percent mark. And it will continue to creep up. Unemployment is thus gradually replacing inflation as the country's biggest macroeconomic bogeyman.

Anyone who closely followed this year's economic forum in Davos knows that this is not just a threat to the Czech Republic, but to the entire international scene. The rise in the Czech unemployment rate can be attributed to the less than rosy situation in industry, which has been experiencing a gradual but long-lasting decline in employment for several years.

Industry is weakening due to relatively expensive energy, emission quotas and the EU's broader green agenda, as well as the rise of Asian competition.

Only some of the employees leaving industry are finding new jobs elsewhere, in the service sector. This year's end of coal mining in the Czech Republic and the acute threat of the end of primary steel production are a bitter reminder that the era of the Czech Republic as a regional powerhouse of traditional industry is slowly but surely coming to an end.

Coal-rich Poland as a leader in performance improvement

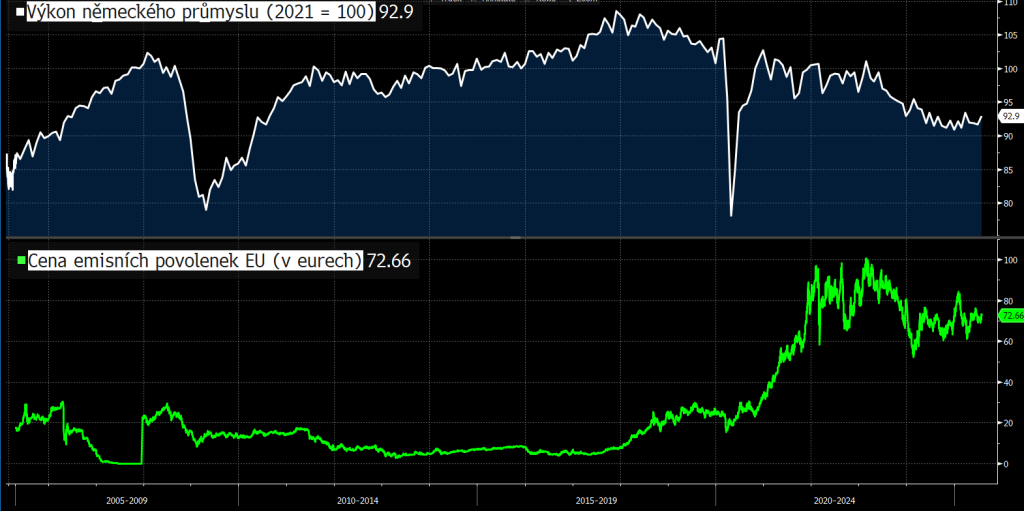

The Czech Republic is threatened by fatal deindustrialization, similar to that which has affected the United Kingdom, France, and Italy in recent years, and which is currently underway in Germany. In Europe's strongest country, the problems facing industry have been particularly evident since the end of the last decade, when the price of emission allowances rose sharply.

Needless to say, the woes of German industry are another source of the sluggishness of the Czech industry and the one in other european countries.

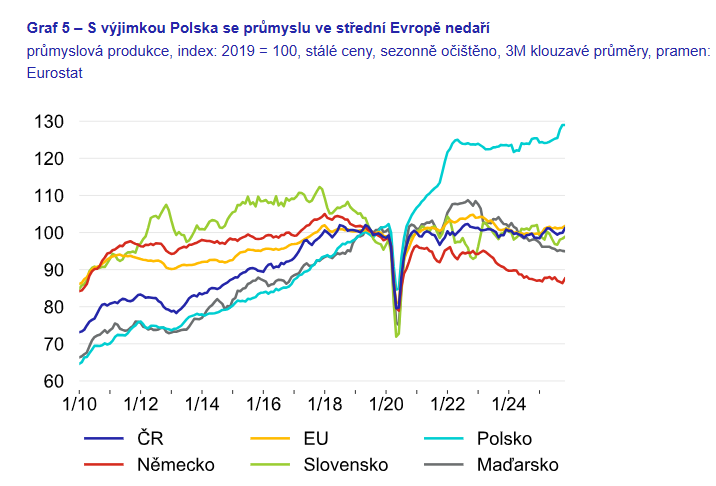

The decline of traditional industry is partly an inevitable consequence of technological progress, but it is also partly the result of the green delusions of the European elites. This is also illustrated by the recently published Report on the Monetary Policy of the Czech National Bank. It shows that Polish industry is by far the best performer in the region in the 2020s.

While EU industry as a whole has been "tucking" around zero since 2019, similar to the Czech Republic, Polish industry has increased its performance by approximately 30 percent in constant prices. German industry fell by more than a tenth over the same period.

This means that it was Poland that significantly reduced its lead in this decade. It is Poland that is sticking with dirty coal for as long as possible. It is Poland that supplies coal to the Czech Republic – all the more so since coal mining has ended in that country. Poland, which has not succumbed to anti-nuclear madness like Germany, is going to build its first nuclear power plant in cooperation with the Americans.

Brussels' U-turn

Poland's restraint towards green ideology helps to hold up a mirror to Brussels. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen made no mention of climate change in her speech in Davos this year. This is an unprecedented change, especially compared to the turn of the decade. At that time, the Davos event was nicknamed the "world environmental forum" for a certain period, as it listened enraptured to the advice of schoolgirl Greta Thunberg.

It is clearly no coincidence that after this year's Davos forum, French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Friedrich Merz began to criticize emissions allowances, the hitherto untouchable "sacred cow" of the progressive elites.

But these elites, including those in Davos, are beginning to fear for the sinking European industry, which is perhaps only resisted by "reactionary" Poland. They have pushed things too far.

Deindustrialization, combined with a costly green agenda, is causing a crisis in the standard of living of a significant part of the population on the old continent, which could sweep away the existing order and threaten the good "livelihood" of the progressive elites themselves.

The deepening political polarization of Europe has clearly frightened even the ivory tower in Brussels. The question is whether it is already too late and whether historical movements have gained so much momentum that they will ultimately "sweep away" Brussels as well. At least in the form we know it.

After all, the Davos Forum, which has considerable informal influence on the European Commission, is already "singing" to a new tune. Brussels will probably soon adopt this tune as well. And not only in terms of rethinking the green agenda, but also immigration.

Alongside the over-stretched green agenda, mass immigration is clearly posing an increasingly obvious threat to the position of the existing elites. For example, according to a new study by the Resolution Foundation think tank, a typical British household with a lower income will have to wait 137 years for its standard of living to double.

That is more than three times longer than it was until recently. It is no longer true that children are better off than their parents. Nor is it true that grandchildren are better off than their grandparents. This is a completely new phenomenon in modern Western history, which will most likely mean a fundamental, even revolutionary social change with far-reaching consequences. That is why there was silence in Davos about climate change, and why warnings were issued there about mass immigration.

A new wind in Davos

That's right, another Davos "certainty" of recent years, the invocation of the benefits of immigration, has definitely fallen this year. Countries that have not allowed mass immigration into their territory will be better prepared for the technological revolution, the advent of robotics and artificial intelligence, said Larry Fink, head of BlackRock, the world's largest investment company, in Davos. And after Klaus Schwab's departure last year, he is also the "boss" of Davos as a whole.

Fink's words were supported at the same forum by Alex Karp, head of the influential corporation Palantir, whose software and technology products are used by armies, including the US military, intelligence services, and police for analytical work so extensively that some even attribute global ambitions to it.

Both Fink and Karp have invested heavily in various forms of artificial intelligence. However, in order to profit from it, its consequences must not drive rebellious masses onto the streets. They now see mass immigration not as a source of cheap labor, but as a risk factor that could multiply the number of rebellious people on the streets.

They sent a clear message from Davos to Brussels. We can therefore expect the European Commission to change its position not only on the green agenda, but also on immigration.

This abridgedtext was originally published on the website lukaskovanda.cz.