Washington. The renewed visibility of religion in the political life of the United States appears unsettling from a European perspective. Prayers at the beginning of government meetings, biblical references in official statements, religious symbolism in public institutions: what has become more conspicuous in the US under President Donald Trump is often regarded in Europe as a regression to pre-Enlightenment politics. Critics warn of an erosion of the separation between church and state, some even of a creeping theocracy.

Yet such reactions reveal less about developments in the United States than about Europe’s own self-conception. They point to a profound misunderstanding of what religious presence in the public sphere entails – and of the role religion can play in sustaining political order. The central question is not whether the state should be religious. It is whether the state remains capable of articulating a normative self-understanding at all.

The American shift: visibility without theocracy

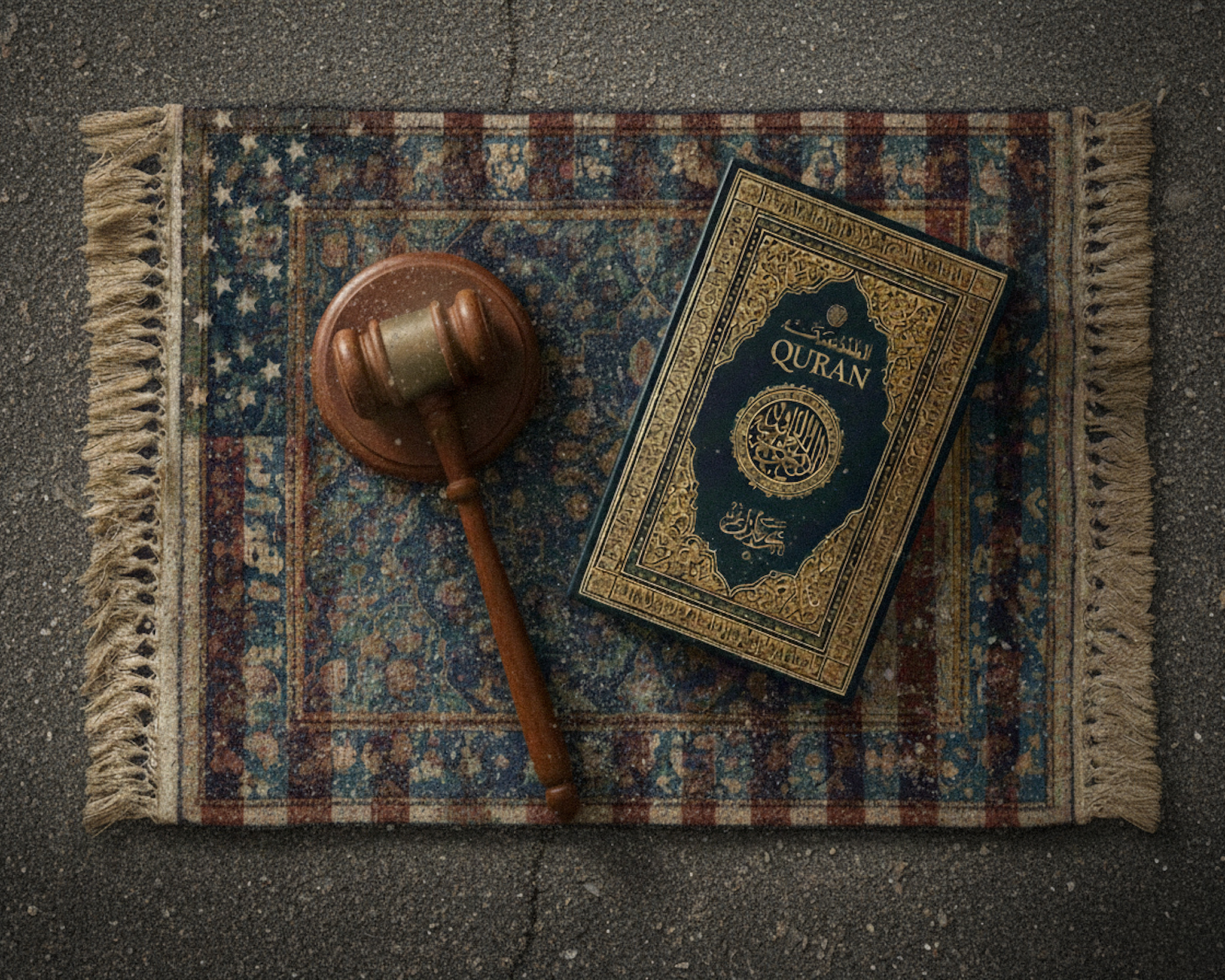

What is currently unfolding in the United States is not religious legislation. American criminal law is not derived from biblical commandments, nor has theology replaced parliamentary decision-making. The United States remains a secular constitutional order, governed by civil institutions and positive law. Neither the Old nor the New Testament serves as a source of law.

What has changed is the understanding of what the separation of church and state entails. For decades, the principle was interpreted defensively: religion was to be kept out of state institutions as far as possible – no prayers, no symbols, no religious language. That restrictive reading is now giving way to a more permissive one. Religion may be visible in public institutions without exercising control over them.

This shift has been reinforced by case law. Over the past decade, the US Supreme Court has increasingly protected religious expression in the public sphere. The state is not required to promote religion, but it is not obliged to suppress it either. Neutrality, in that understanding, does not mean absence, but equal accommodation.

This distinction is frequently overlooked in Europe. The American debate is not about religious homogenisation. It concerns whether the state recognises religious convictions as legitimate components of public life or confines them strictly to the private realm.

Europe and the illusion of worldview neutrality

Europe, by contrast, has largely embraced a different model. Religion is treated as a private matter, at best as cultural heritage and often as a disruptive force. Christian symbols are removed from schools and public buildings, and religious language is excluded from political discourse. The state presents itself as worldview-neutral, but in a particular sense: neutral through abstention.

This posture is commonly equated with modernity and tolerance. In practice, however, it creates a normative vacuum. A state that refrains from any cultural or moral self-description relinquishes the capacity to formulate expectations of its citizens that extend beyond the purely legal.

It is often overlooked that even states committed to secular governance are not necessarily devoid of a worldview. Germany’s Basic Law opens with an explicit reference to responsibility “before God and man”. This does not establish a theocracy, nor does it grant political authority to any church. It marks a theoretical boundary: the state acknowledges that it is not the ultimate arbiter of truth, dignity or morality.

Germany is not alone in this respect. Poland’s constitution refers to God, as do those of Ireland and Switzerland. France’s strict laïcité represents a different tradition. Europe is not religiously uniform - yet in political practice many European states have drifted towards a form of functional secularism that increasingly treats religious reference itself as suspect.

An asymmetrical approach to religion

This restraint, however, does not apply equally to all religions. While Christian symbols and arguments are frequently portrayed as outdated or exclusionary, religious demands advanced by Muslim actors are often approached through the lens of cultural sensitivity. Headscarf debates, mosque construction and religion-based exemptions are regularly framed as expressions of pluralism.

The result is an asymmetry. The state retreats from its own religious and cultural tradition while actively protecting religious identity among minorities. The imbalance has political consequences. Religion becomes politically effective where it is articulated most assertively, while the state itself lacks a normative language of its own.

Political Islam is not merely a theological phenomenon. It is an ordering project that explicitly links religious norms to political authority. Where the state understands itself primarily as a neutral administrator rather than as a cultural framework, such projects encounter little resistance – not because they are welcomed, but because the state lacks conceptual confidence.

Political Christianity? An uncomfortable possibility

Against this background, a question long avoided in Europe gains urgency: could a politically articulated Christianity offer an alternative?

This does not imply theocracy, biblical law or religious coercion. What is at stake is the re-emergence of Christianity as a cultural and normative reference point for statehood – as a source of human dignity, responsibility, guilt and limitation. It would provide a framework explaining why freedom is not absolute and why the state may legitimately articulate expectations of loyalty and integration.

Such a form of political Christianity would not empower the church as a governing institution. It would function as a form of societal self-description. Religion would not become mandatory, but its ordering function would be acknowledged. This is precisely where the difference from political Islam lies, which seeks to translate religious norms directly into law and authority. The American debate demonstrates that the distinction is viable. Religious visibility does not imply religious legislation. The state remains secular, but it is no longer normatively mute.

Europe’s deeper inhibition

Why, then, does Europe struggle to make this distinction? The answer lies less in law than in history. Christianity is perceived as burdened: crusades, colonialism, clerical abuse. This past is not treated as part of Europe’s own historical development, but as a moral liability requiring distance.

Islam, by contrast, is often viewed as external – the religion of the Other – towards which particular caution is deemed necessary. This perspective ignores the fact that political Islam also formulates historical and political claims, albeit without Europe’s inherited sense of guilt.

The result is a paradox. Europe mistrusts its own cultural foundations while extending moral deference to competing normative systems. The secular state does not become neutral as a result; it becomes disoriented.

Not a theocracy, but a state with self-understanding

The renewed religious language within American state institutions is not a blueprint for Europe. Historical and constitutional differences remain substantial. Yet it forces Europe to confront an uncomfortable question: can a state endure if it no longer articulates what it stands for? The alternative to religious self-denial is not a theocracy. It is a state that recognises and names its cultural foundations – a state that neither instrumentalises nor suppresses religion, but understands it as part of its historical and normative order.

Europe can either engage in this debate or continue to avoid it. Political Islam will continue to offer order regardless. The question is whether the European state will be able to respond with anything other than silence.