Although ANO saw its support decline from an initial 40 percent to a final 34.51 percent as the votes were counted, this development was to be expected. Traditionally, the results from the large cities, where the movement has weaker positions, are counted last.

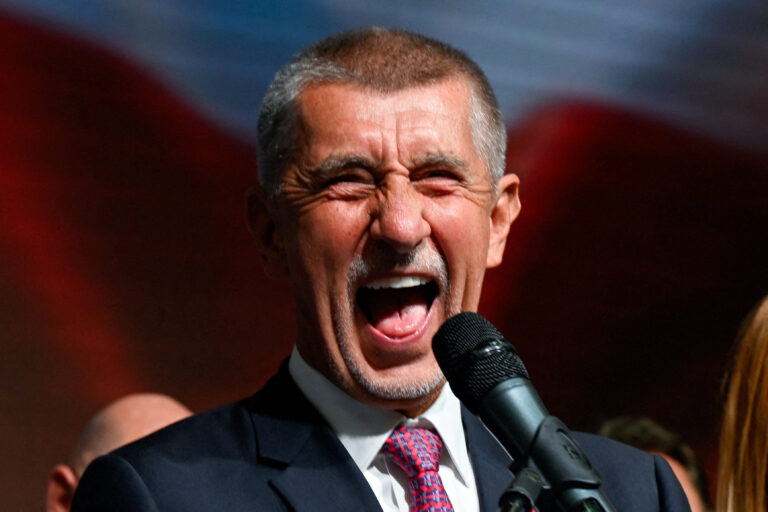

The difference between the capital and the rest of the republic was once again evident—the Spolu coalition only won in Prague. However, Andrej Babiš has no reason to be sad. His movement achieved the best result in its history.

Its chairman and political advisors responded excellently to the current situation. While the former ruling parties campaigned with the slogan “Everything is at stake,” Babiš remained calm. He offered his voters exactly what they wanted to hear: that everyone would be better off and that he promised everyone “more money.” The Czechs vote primarily with their wallets, which Babiš understood perfectly and exploited.

The main theme of the outgoing ruling parties' campaign was a warning narrative about the rise of populists who could allegedly drag the Czech Republic “somewhere to the East.” However, this term was vague and was often only clarified with the warning that “we don't want to end up like Slovakia or Hungary.”

Such comparisons were misleading, however, as they ignored the historical development and political peculiarities of these countries. In the chaos before the elections, when the media was constantly defending democracy and its values, Andrej Babiš found his way perfectly.

He offered voters security: the world may not be perfect and morally flawless, but it will be “ours” and stable. Babiš took advantage of the fact that human memory tends to repress bad memories and emphasize good ones. He managed to give voters the impression that he could take the country back to the pre-Covid era, when – apart from the chaotic period of the pandemic, which, incidentally, was not handled well by political leaders worldwide – it had a positive economic record.

Although this was based more on the favorable economic context than on his personal abilities, it was a time of relative calm. The war in Ukraine was low-intensity, the energy crisis was not yet known, and inflation remained within the two percent target. Babiš made the most of these distant memories to win the election.

Nostalgia instead of ideology: the recipe for success

The desire for stability brought the ANO movement an unexpected number of voters. The elections also showed that the Czech people do not want radical anti-system solutions.

It came as a big surprise that Kateřina Konečná Stačilo's left-wing group failed to make it into parliament at all, even though most polls had predicted its success. Parties that espouse traditional left-wing values have not been particularly successful in Czechia.

Unemployment remains relatively low, and the poorer working class sees the solution more in Andrej Babiš, who promises his voters that they will do well if he does well. People have traded their demand for more radical change for the promise of a low-paid but secure job.

Okamura's SPD cannot be satisfied with the result either. After four years in opposition, it had expected a better result than 7.7 percent. The issue of fighting Ukrainians, who allegedly take away jobs and housing from Czechs, did not go down as well as the party had hoped. This narrative resonated more two years ago. As with the Stačilo movement, people ultimately prefer maintaining the status quo to radical change.

The elections in Czechia have shown that society is not yet ready for anti-systemic solutions. The system may not be perfect, but most people continue to tolerate its shortcomings in exchange for apparent stability and consistency. The Czechs are not revolutionaries.

Motoristi on the rise

The decision to moderate, on the other hand, paid off for Motoristi. A few months before the elections, they emphasized that they were not a staunchly anti-system party and did not question NATO or the European Union. On the contrary, in their opinion, the EU needs reform and NATO should be more in line with the goals and intentions of US President Donald Trump, whose policies Motoristi support. To this end, they emphasized traditional right-wing values, appealing to disappointed ODS voters. These votes were then lost to the Spolu coalition.

Overall, it can be said that in the elections, the Czechs opted above all for a nostalgic return to the recent past. The question remains whether this attitude is sustainable in a rapidly changing world. Andrej Babiš promised voters the moon without clearly stating where he would get the money for his plans.

His solution in the form of more efficient tax collection and combating the shadow economy is commendable—taxes can indeed be collected more efficiently. But even the best tax collection is not enough to cover the current budget deficit. The Czech government is already suffering from a lack of funds, let alone being able to afford to increase civil servants' salaries or significantly reduce waiting times in the healthcare system, as Babiš promised in his election campaign.

Coalition puzzle: pragmatism versus values

Babiš may try to form a single-party government, but with only 80 MPs, it is unclear how he could win the confidence of parliament.

An obvious option would be a coalition between ANO, the Motorists and the SPD, which would have a comfortable majority. However, the problem lies not in the number of MPs, but in the difficulty of reconciling the parties' programs.

ANO pursues pragmatic policies, while its voters do not expect a value-based approach. However, this style is problematic for potential coalition partners who, on the contrary, advocate value-based policies. The Motorists want to be a classic right-wing party, while the SPD wants to be a national party.

This poses a considerable risk for both parties. If they adopt the pragmatic style of Babiš's movement and put their values agenda on the back burner, they run the risk of losing part of their identity in the next elections—and with it, voters who expect them to pursue clearly defined policies.