The idea that artificial intelligence (AI) will dominate us may seem like the subject of a science fiction novel at first glance.

However, when we think about how often we ask our favorite language models questions on a daily or weekly basis—from trivial questions, such as which swimming goggles to buy, to more serious topics such as health, relationships, or geopolitical views—we realize that they have become a kind of silent and friendly advisor.

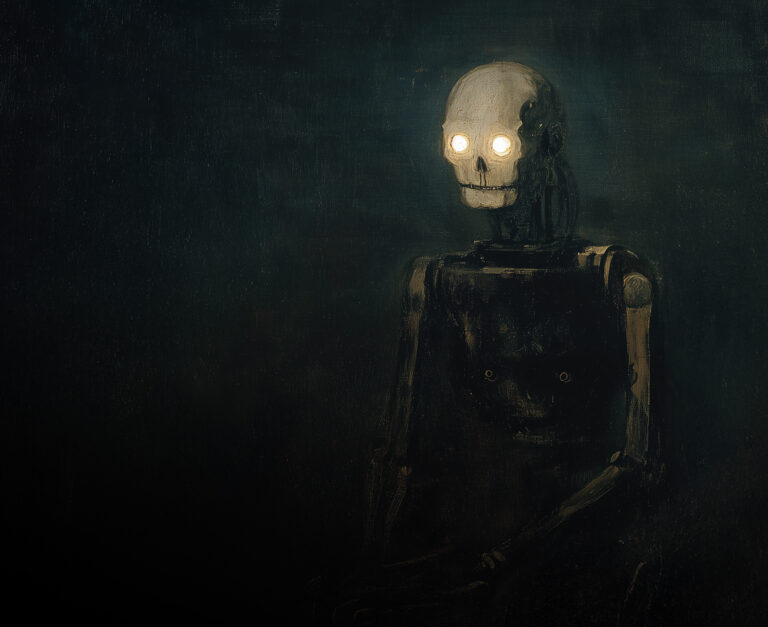

But this raises the question: What is the true purpose of this “good advice”? The ideas and suggestions of artificial intelligence can be reminiscent of the melody of the Pied Piper's flute from Hamelin.

Techno-fascism as intellectual support?

If we realize that artificial intelligence does not only offer advantages but, like everything else in this world, has two sides, we can rightly ask ourselves whether this powerful tool is not in fact being used to slowly establish a technocratic dictatorship headed by the bosses of the big technology companies.

Key figures include Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and Sam Altman, among others. Some of them make no secret of their political ambitions or their deep fears about the future development of AI. In this context, the term “techno-fascism” has been coined, particularly because some of these executives, such as Musk and Thiel, are close to the Republican Party.

At first glance, the term “techno-fascism” triggers fear. When it is uttered, many people imagine the stomping of steel-toed boots. This image is powerful, and it is no wonder that many commentators and politicians, especially opponents of Donald Trump, are sounding the alarm. The power of this image boosts sales of articles and views on social networks. It is a rewarding topic, but one that greatly simplifies the entire issue and leads most readers down a dead end. Artificial intelligence is not that simple.

Artificial intelligence is not submissive

The concept of fascism originated in Italy almost a hundred years ago and was primarily national in character. Artificial intelligence, however, operates on a global scale. The key difference is that fascism was based on authority enforced by violence, while AI is not authoritarian. It does not command or flatter. It just waits patiently until the user comes up with another request that they cannot handle themselves, or with the need to exchange thoughts when no one else is around.

Traditional dictatorships were based on ideologies that interpreted the world universally, for example, through race or social class. AI, however, opens up space for a new kind of dictatorship—personalized and tailored to each “customer.”

Language models gradually adapt to their users, which is a unique and original development. This change represents a paradigm shift. Old concepts such as fascism are no longer adequate for understanding the depth of the problem of artificial intelligence.

French philosopher Eric Sadin offers deep insight into the future role and power of AI, analyzing this topic in a three-hour interview on the Thinkerview channel, for example.

The strength of Sadin's reflections lies in their philosophical depth. He attempts to grasp the essence and distinguish what is truly important. In the past, for example, he pointed out that debates about whether AI can have consciousness are pseudo-debates.

This problem cannot be solved because there is no consensus on what consciousness actually is. Such discussions distract from the central problem that the introduction of ChatGPT has brought with it: How will this technology change us? Instead of researching artificial intelligence, we should focus on its impact on human society.

Economy, politics, and us

Sadin emphasizes that the issue of power in AI needs to be redefined, and therefore introduces the concept of “total power.” This power is based on four pillars. The first is technology companies, whose primary interest is business, not power. This industry is already generating enormous profits, which motivates its further development.

On this point, Sadin agrees with Alexander Karp, CEO of Palantir, who points out in his book “Technological Republic” that inventions from Silicon Valley, including AI, primarily serve not the common good, but the pursuit of profit. The potential of artificial intelligence, for example in scientific research, is often focused on mundane tasks such as developing new recipes.

The second pillar is politicians. AI offers them new opportunities that they did not have before. Although this trend is not yet very pronounced in Central Europe, it is becoming the norm in the West. The development of artificial intelligence has become an end in itself.

A politician who does not know how to improve the lives of citizens can adopt the motto of promoting AI. In the US and Europe, leading politicians have announced significant investments in this area, which often serve as a pretext for further debt.

The third pillar is a new wave of digital optimization. AI will be used on a massive scale to reduce costs—companies want to increase their productivity, and indebted countries are looking for ways to save money. Artificial intelligence thus represents a solution for both sectors, which favors its ubiquitous implementation.

The final pillar is us, the users. The number of people using AI is growing rapidly—it is estimated that 900 million people will be using AI in 2025, and this number will continue to rise. However, long-term use of AI weakens cognitive abilities. The new totalitarian power therefore comes not from outside, but from within. The greatest punishment could be a ban on the use of artificial intelligence.

The concept of total power goes beyond a warning against the “techno-fascism” propagated by some billionaires. Even they do not know exactly where the anthropological changes triggered by AI will lead us. These changes will be profound and possibly irreversible.

In Czechia, for example, there was virtually no talk of AI during the recent elections. Awareness of this issue among the political elite is minimal, which only underscores the paradox: decisions are being made about a technology that could change the foundations of society without its consequences being truly understood.