The European Union has found its modern equivalent of medieval indulgences. This time, it is not letters from Rome that are being sold, but "green indulgences" from Brussels – emission quotas.

Every ton of carbon dioxide has its price, and whoever emits it must pay a penalty. The main thrust of the emission quotas defends this moral line. However, it is not just a matter of punishing sinners by making them pay more, but also an educational tool.

The higher mission is to educate industry and households to behave more economically. However, behind this mask of noble interests lies a pragmatic reality. In fact, emission quotas are nothing more than a tax to finance the functioning of the European Union.

Emissions quotas will in fact contribute to strengthening the power of Brussels, which will gain independent resources for its functioning. It is not just a question of functioning, but thanks to the money raised, the EU will finance its plan to transform the lifestyle of most Europeans under the pretext of ecology.

To be precise, from 2021 onwards, the EU will be entitled to a quarter of the proceeds from quota auctions.

Extension of the ETS system: increasing the power and profits of the EU

The new extension of the ETS 1 system to ETS 2 will further consolidate this system and increase the profits of the European Union. However, the change to this system is limited by good intentions. The ETS 1 system covered approximately 40 percent of emissions in the EU – mainly energy, industry, and aviation.

The expansion to heating, fuels, and smaller sectors is expected to cover up to 75 percent of emissions in the EU. The main argument in favor of introducing new quotas is the 40 percent reduction in emissions since 2005 in the sectors covered by ETS 1. At first glance, this sounds like great news. However, this reduction is not solely due to companies switching to cleaner and more environmentally friendly production.

The question is whether this change has been achieved through the deindustrialization of Europe, i.e., the closure of companies that have moved to other parts of the world where they do not have to pay. The share of industry in the European Union's economy has been declining for a long time, falling from 20.7 percent of GDP in 2005 to the current 19 percent. In France, for example, it has fallen from 19.6 to 17.5 percent in two decades.

In absolute terms, this amounts to hundreds of billions of euros. This trend shows that Europe's industrial base is weakening, even at a time when it is facing the greatest transformation in its history – the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Emissions allowances as a commodity: market problems

If we accept the existence of ETS 2 emissions allowances as a necessary evil, we encounter another problem. Emissions allowances function as a commodity on the stock market. In other words, their final price is determined by the market.

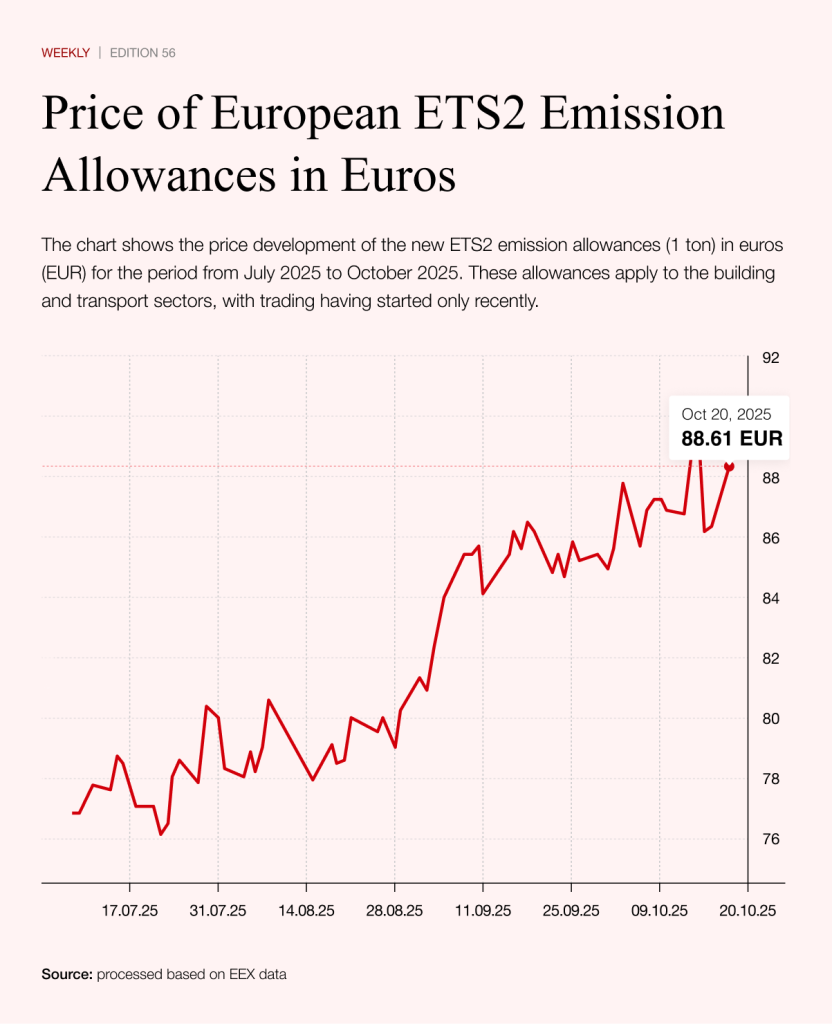

These allowances are traded primarily on the Leipzig exchange, and since 2022 their price has fluctuated between €60 and €100. This is relatively high volatility. As this is a market mechanism, the EU has no way of directly influencing this market. In the event of high prices, it may decide to issue more quotas in the coming period, thereby lowering the price.

The word "may" is important here. If there is insufficient political will or if the Union does not take sufficient action, we may face similar problems to those we experienced on the Leipzig electricity exchange. Market mechanisms should work to stabilize the price of allowances. However, this does not mean that we will be spared market turbulence.

The second problem, which is perhaps more serious than market turbulence, is that the volatility of allowance prices makes it impossible to accurately estimate the impact of the introduction of ETS 2. This makes it impossible to have a rational debate on the subject.

PwC has prepared a study estimating the costs of the impact of the introduction of ETS 2 quotas on Czech households between 2027 and 2032. It works with two scenarios: a quota of €45 and €75. The PwC scenarios anticipate increased household costs of CZK 300 to CZK 500 (up to €20) per month, or up to CZK 6,000 (almost €250) per year. These costs will be reflected everywhere, so the quotas will be highly inflationary. The main shortcoming of the study is that both scenarios are too optimistic. The current price of the quota is €79, and prices around €100 are not uncommon. This study is therefore overly optimistic.

There are also much more dire scenarios. Czech economist Lukáš Kovanda, for example, predicts that in 2030, the average Czech household will pay more than €3,000 per year due to emission allowances. Slovak Environment Minister Tomáš Taraba agrees with this assessment. He speaks of an absurd system that will charge people for heating their homes and driving to work. "This amounts to as much as €3,000 per year per household," he emphasizes.

The second counterargument is that there is no cap on the price of quotas. Households could thus be regularly impoverished. And the third conclusion that the study clearly shows is that middle-class households will feel the greatest impact.

A surcharge of €200 per month will not really affect rich people. And for the poorest, the EU has the Social Climate Fund (SCF) in reserve, which is to be launched together with the ETS 2 system in 2026/2027. From this perspective, emission allowances are just another tool for redistribution and can also serve to significantly weaken the middle class. But it is precisely the middle class that is important in preventing society from falling into extremism.

The European Union is thus cutting off its own nose to spite its face when it talks about the rise of populism and extremism, while at the same time feeding populism by causing the middle class to disappear. The impact will be greatest on households that heat with gas and have two members who need to drive to work.

The illusion of freedom of choice in climate policy

Ultimately, it turns out that freedom of choice in emissions policy is more of an illusion. What appears to be an individual decision—whether to drive a car, heat with gas, or invest in a heat pump—is in fact framed by policies that increasingly push citizens toward predetermined solutions.

First, you received a subsidy to purchase a new gas condensing boiler, and now you will have to pay for its operation because it is no longer "green enough." And who knows if the same fate will befall heat pumps or district heating in a few years.

European climate policy thus places a heavy burden on individuals, but at the same time avoids answering the fundamental question: where is the line between legitimate regulation and social engineering that, under the banner of green transformation, dictates how people should live?