For many Europeans, the sight of Chinese cities crowded with cameras and residents who never let go of their phones, even though they know that their every word can be overheard, is reminiscent of the dark vision from the novel 1984. Big Brother China watches comfortably and continuously.

The European continent likes to tell itself that this future does not concern it: after all, it is based on the protection of privacy, plurality of opinion, and distrust of centralized power. There is no one-party policy as in China.

And yet, despite the well-known temptation of the state and the absence of anyone to control the controllers, Europe is embarking on a debate about Chat Control—a technology that would turn citizens' private communications into a space for automatic scanning of state-defined content. Proponents defend this idea using the same language as the Chinese communists: they claim it is "for the greater good."

China as an experimental laboratory

The Chinese example shows the great ability of humans to adapt to this social control. Being free and bearing responsibility is a sign of human maturity. However, this burden is heavy. Handing it over to the state is a great temptation. People find convenient reasons, such as that the surveillance system will make it possible to find lost children, detect theft, regulate traffic, and suppress crime. Basically, the same thing that every politician promises. A safe state.

However, the Chinese system is not just about controlling and catching criminals or potential political dissidents. Constant scanning of the population and its communications allows the system to "read" the mood of the population and then use it for further manipulation. This reinforces the role of the state as a good father who cares for everyone.

The system can estimate what is currently troubling the population, such as poor access to medical care in a particular region. The state can respond to this even before anyone dares to file an official complaint. Thanks to this, it slowly but surely gains the trust of citizens that everything can be solved thanks to state supervision.

In such a system, citizens can ultimately be sure of one thing: that the state knows what is troubling people even before they begin to feel it. This is the dream of every government official.

However, the Chinese state has a powerful tool at its disposal: it no longer needs to persuade individuals when it controls the masses. Individuals will follow the herd anyway, thanks to our natural instinct. Social networks are like a shared thermostat regulated by the state.

All it takes is a slight adjustment of the algorithm in the right direction to make it clear how the masses should behave. Of course, this method of government also has a downside. That is self-censorship.

This does not take place as it used to in totalitarian regimes, i.e., in front of other people, such as colleagues at work, but in the mind of the individual. What they can and cannot think. This divided state of mind has an impact on a person's psyche.

However, such regimes are not concerned with the mental state of the individual. They are concerned with maintaining economic performance. In many professions, this is certainly possible, but in those that require creativity or freedom of spirit, it is very problematic. If an individual's personal creativity, which necessarily requires freedom of thought and therefore the absence of self-censorship, cannot develop, then ultimately their personal economic potential cannot be fulfilled either.

A civilization of privacy that forgets where it came from

Europe, at least historically, has followed the opposite logic. Especially in Catholic Europe, the confessional was a place where no one had the right to listen. The seal of confession is older than most European states.

The Church was thus one of the first institutions to recognize that people need a space where they can say anything without being watched. They could relieve themselves of what weighed on their conscience and at the same time be sure that it would remain hidden forever. Often, these were serious matters.

Without this practice, however, spiritual growth is difficult. Confession reminded everyone of our shared fragility, which does not need to be made public in order to be healed. This tradition survived secularization, the Renaissance, and modern democracy. Europeans understood that transparency is for states, not for individuals.

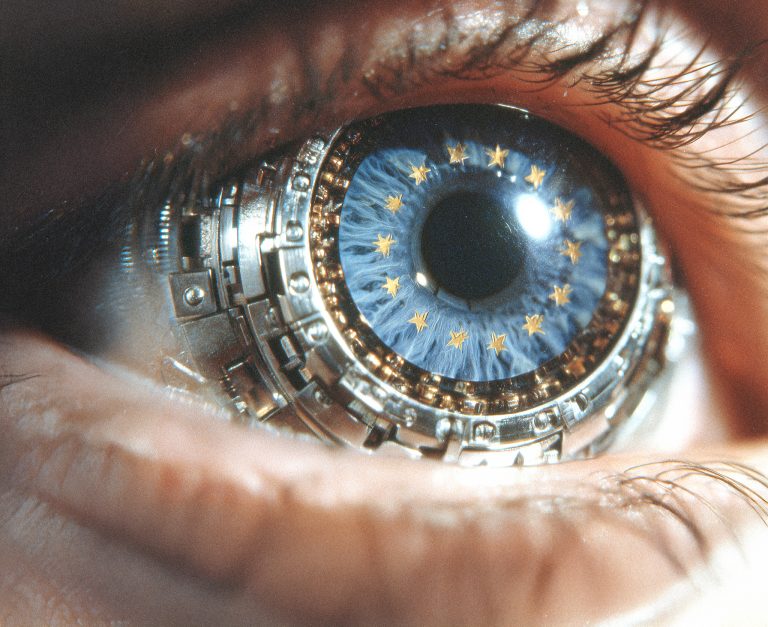

Chat Control, however, turns this logic upside down. Europe is thus consciously divesting itself of its identity. This technical means introduces a client monitoring mechanism. All photos, videos, or texts are checked before they are sent.

Services that were built on encryption are being transformed into systems that provide the state with content before it is encrypted. The content is compared to a pre-prepared database of digital fingerprints, which is designed to identify prohibited material before the message is even sent.

However, once the principle of encryption is violated even once, the state can expand the scope of harmful information. After pedophilia, terrorism will surely follow. After terrorism, the fight against disinformation will follow. And after the fight against disinformation, the fight against all opinions that divide society will follow. Only unity of opinion will ensure national, in this case European, security. The specter of an Orwellian regime is thus becoming more than clear.

Moral arguments that obscure the essence of the problem

Proponents of Chat Control primarily resurrect moral arguments in their defense. It is difficult to argue against the protection of children. However, these advocates deliberately circumvent the technical essence of the problem with their moral arguments. This is not targeted scanning, but blanket scanning.

All information will be linked to a database. For the algorithm to be effective, it must, in principle, go through all messages. It is an X-ray of the whole society. There are other ways to protect children than introducing an X-ray of the entire information flow.

The irony is that this step comes after it has been proven that social networks collect data that is used to manipulate users. This data collection can be hidden under the guise of advertising optimization.

Many scandals have shown that social networks are capable of fundamentally influencing election results. Not only that, social networks are behind the return of censorship to the public sphere. Many people experienced this during COVID, when a few inappropriate posts could result in the deletion of an entire account. This problem also affected well-known and influential accounts.

Many people have since learned their lesson and understood that these platforms are not entirely free places to exchange opinions. And so people have resorted to discussion groups via WhatsApp, Signal, or Telegram. These groups have become a place where people can more freely share their content, insights, and opinions.

This island of freedom is now coming to an end. More precisely, a few lines of computer code separate us from a fundamental change in society. Once the state starts controlling our private communications, there will be no turning back.