On Monday, US financial markets were closed for a public holiday commemorating Martin Luther King. It is ironic that on the anniversary of a man who promoted dialogue and opposed brute force, Donald Trump significantly escalated his demands on Greenland.

He also threatened to impose tariffs on any country that tried to prevent him from doing so. European countries that sent their troops to the island were to be punished from February 1. However, Europe has not allowed itself to be intimidated, at least verbally, and has promised Trump retaliation.

As a master negotiator, Trump actively seeks out these moments, escalating his threats and waiting to see how far the old continent will go.

Market reaction to Greenland threats

The markets' reaction to these dramatic moments was not long in coming. The prospect of a second major trade war unsettled the markets.

Moreover, from an economic point of view, the US president is taking a big risk. This is because last week China negotiated with Canada on expanding trade cooperation, and French President Emmanuel Macron in Davos practically called on China to trade even more with Europe. The country of the dragon will certainly not miss out on these offers.

The markets do not care how these overtures to China turn out, because the immediate effect is uncertainty and unpredictability. And it is precisely these factors that have a negative impact on the stock markets, regardless of what is happening in the real economy.

Unpredictability and fears of escalation between Europe and the US have driven stock markets on both sides of the Atlantic into a sell-off after a long period of stability. A trade war is much more likely than a conventional conflict. Threatening military confrontation on the part of Europe makes no sense, because the vast majority of European countries' military equipment comes from the US, the very country with which they would want to wage war.

These challenges and speculations about military conflict simply have no basis in reality. However, a trade conflict is something else, because the United States has already imposed its tariffs and Europe is only bearing them for now. No significant response has come from Europe yet.

A symbolic gesture and the bond market

A possible way forward was shown by the Danish academic fund AkademikerPension, which decided to divest itself of US bonds worth $100 million in its portfolio.

This sale is only a drop in the bond ocean—the daily volume of US bonds traded is $900 billion, so it could not be reflected in the price. However, it was a symbolic gesture that forced investors to think about what would happen if all investors started to get rid of US bonds.

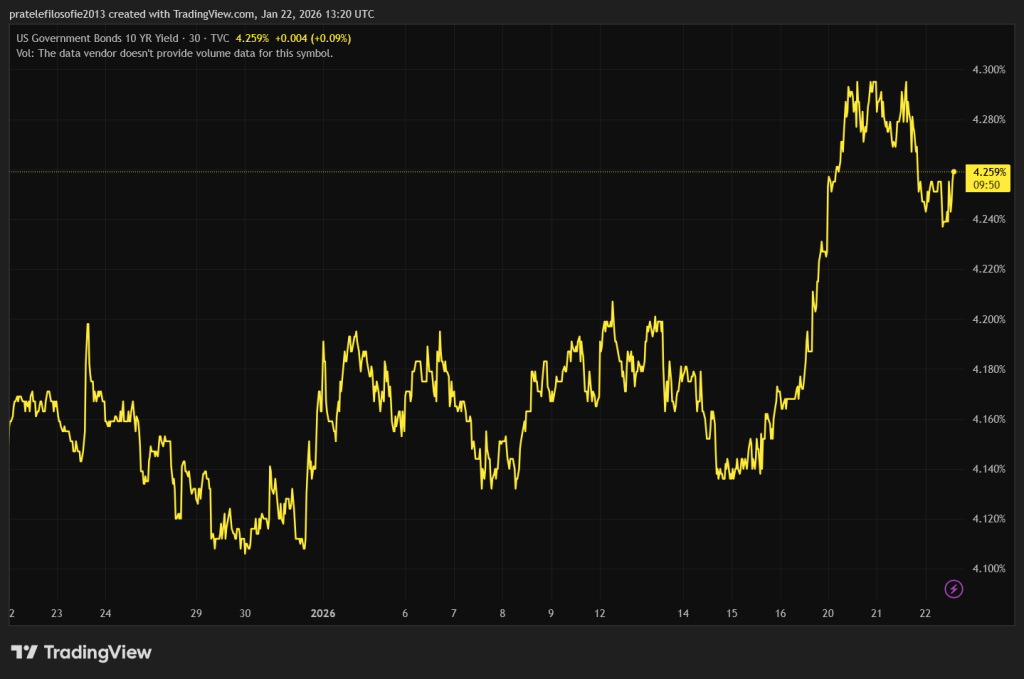

Ten-year bond yields therefore began to rise. For the Trump administration, it was an unpleasant déjà vu: US stocks are falling and bond yields are rising. If the markets were functioning normally, the direction would be the opposite. Investors would try to hide from risky stocks in safe US bonds. When this mechanism stops working, something is fundamentally wrong in the markets.

Trump understood the signal. In Davos, he showed his typical TACO [an acronym forTrump Always Chickens Out, editor's note]. Suddenly, he never mentioned the tariffs imposed on Europe, no one wants an escalation of tensions around Greenland, and everything will surely be settled. Wall Street won.

American indices are green again. The Trump administration tried to dispel these concerns by claiming that developments in Japan were primarily responsible for the situation. Yes, Japan is currently exerting overlooked pressure on global markets, but no one doubts that the main driving force remains the White House chief and his social media account. Trump's weakness remains the financial markets, both stock and bond.

The problem with the stock market is that all the big players have bought in. With the exception of Berkshire Hathaway and a few other funds, the vast majority of funds are invested. A fall in the US stock market would be a disaster for everyone.

Moreover, there is a real threat that if several crashes like the ones we experienced this week are repeated, investors will find that they no longer have the funds to drive the markets up. And that is when we will experience a more significant correction.

Japan and its own brake

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaiči did what she promised and dissolved parliament. The country is thus heading for early elections, which will take place on February 8. The main reason is to strengthen her mandate.

She wants to continue with a loose monetary policy to support Japanese exports in particular. This, of course, pleases the Tokyo Stock Exchange. However, Japan has been pursuing a loose monetary policy for decades and has accumulated enormous debt. The prime minister is thus going against the tide.

Instead of tackling inflation and reducing debt, she is heading in the opposite direction. The Bank of Japan recently raised interest rates to curb inflation, but at the same time made it clear that monetary policy is still not restrictive enough. It would be sensible to focus on inflation and debt reduction.

However, nothing will stop the prime minister from pursuing her plan. She is going into the early elections with a program that proposes reducing food taxes. This will deprive the budget of further revenue. When a country is heavily indebted, it should strive for the exact opposite. This radical effort to act while ignoring the debt issue ultimately frightened even the Japanese stock market, which had previously welcomed the prime minister's actions.

We will see if, as with Trump, the bond market will act as a brake. Yields on Japanese ten-year bonds have shot up to 2.38 percent. That is a very interesting yield. It does not yet cover current inflation, but if the trend continues, Japanese bonds will gradually become more attractive.

And that is precisely the risk that the Trump administration is talking about: the Japanese will no longer have to buy US bonds to invest their money safely and with relatively high yields.

However, rising yields on Japanese bonds also have a downside for Japan itself. Given its huge debt, even a small increase in yields will have a very negative impact on the state budget.

How will Japan repay its huge debts? And when we add US debt to Japan's debt, it comes as no surprise that gold and silver have strengthened significantly this week. Gold is now very close to breaking through the psychological barrier of $5,000 per troy ounce.