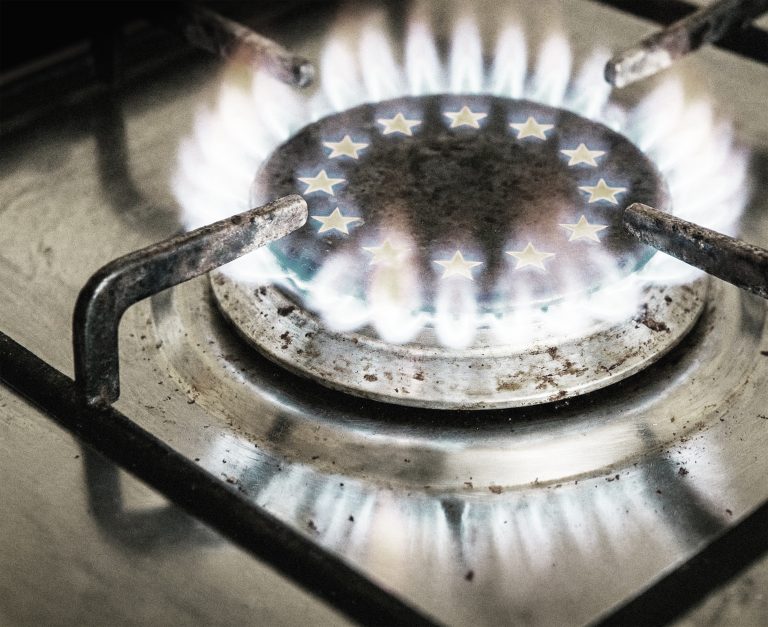

Most motorists know how much a liter of gasoline or diesel currently costs at the gas station. After the recent energy crisis, in which the price of gas played a major role, many people now know how much a kilowatt-hour of electricity costs. However, there is not yet such widespread awareness of gas prices.

Of course, it depends on what you use to heat your home. Yet gas is a strategic raw material that has a direct impact not only on household bills, but also on the functioning of industry, the stability of energy networks and, ultimately, the political and economic security of Europe.

Understanding gas prices is therefore essential to understanding why Europe is nervous about energy today, why political decisions are increasingly being made on the basis of supply issues, and why energy has become a topic of high politics.

Hidden power

Gas is the invisible energy of everyday life. Most households use it to heat water, cook, and, above all, to heat apartments and houses, i.e., for activities that we take for granted as long as they work. Households account for approximately 35 to 40 percent of total gas consumption in the European Union.

Consumption of this commodity is highly seasonal and most dependent on winter. Heating alone accounts for approximately 62 percent of gas consumed in households. Every colder winter is thus immediately reflected not only in household bills, but also in tensions across the European energy market.

Heating bills also contribute to social tension, and it is this aspect of the gas story that is most closely watched politically. In reality, however, it represents only a fraction of total consumption. Another 30 to 35 percent of gas is consumed by industry, mainly in the chemical and paper sectors, but also in steel and iron production, where gas serves not only as an energy source but often also as a raw material.

The least visible, yet strategically crucial part of gas consumption—roughly 25 to 30 percent—is its use in electricity generation in gas-fired power plants. These have one key feature: they can be switched on and off quickly, regardless of the weather.

This is why they function as a regulatory element of the electricity system and are an essential complement to renewable sources, whose production depends on current weather conditions. Gas-fired power plants thus ensure the stability of the transmission system at times when the sun is not shining and the wind is not blowing.

The increase in gas prices in 2022 was one of the main reasons why Europe found itself in an energy crisis. The price of electricity on the European market is based on the costs of the most expensive source needed to meet demand, which was gas-fired power plants.

The pressure on gas prices is therefore politically stronger than for oil or electricity, as gas affects households, industry, and public finances at the same time. It is a key source of heating in winter, an irreplaceable raw material for part of industry, and at the same time an item that states must subsidize or regulate in times of crisis.

From pipeline to liquid

For many years, Europe met its demand for natural gas largely through supplies from Russia. This model collapsed not only figuratively with Russia's invasion of Ukraine, but also physically when the Nord Stream gas pipelines were damaged by sabotage in 2022. Russian gas had several key advantages for Europe, namely low transport costs, relative price stability, and the possibility of concluding long-term contracts.

The result was a regional gas price shaped primarily by bilateral relations between Germany and Russia, not by the global market. For Germany, cheap Russian energy became one of the cornerstones of its industrial model and competitiveness, especially in energy-intensive industries.

The collapse of this arrangement therefore meant not only a change of supplier, but also an intervention in the very foundations of European and, above all, German economic strategy. Europe was thus forced to quickly replace the regional pipeline model with a global market for liquefied gas.

The transition from pipeline gas to liquefied gas meant a fundamental change in Europe's energy logic. LNG makes it possible to import gas from all over the world, not just from regional suppliers, but at the cost of a complex and expensive process.

The gas must first be liquefied, then transported by ship, and finally converted back into a gaseous state upon arrival. In addition, the price of shipping is somewhat volatile, as it depends on current demand.

The price of gas is therefore no longer primarily determined by regional agreements, but by global demand, logistics, and geopolitical events far beyond the continent's borders. Europe has thus become primarily a competitor to Asia, which has been buying liquefied gas for a long time.

Dependency still exists

Europe has not rid itself of its dependence on gas, but has only changed the way it approaches it. The transition to LNG has brought flexibility to the old continent, but also higher prices and global uncertainty.

New map of European gas

After the collapse of the Russian pipeline model, the structure of European gas supplies has changed fundamentally. Norway has become the main supplier of this commodity in pipeline form, today providing the largest share of stable flows to the European Union. Norwegian gas is a relatively reliable and politically secure source, but its importance is limited by natural constraints. Production is based on mature fields [gas fields that have been exploited for a long time and are in the late stages of their life cycle, ed.], and further increases are limited.

Other pipeline supplies come from Algeria and Azerbaijan, regions that help Europe diversify its sources but cannot meet European demand on their own. Their role is important, but structurally complementary. Liquefied natural gas has therefore become a key element in the new European energy equation. LNG from the US and Qatar now accounts for a significant share of imports and allows Europe to respond flexibly to disruptions on individual routes.

The UK plays a special role in this new architecture, having become an important transit and trading hub thanks to its infrastructure and connections with continental Europe. Part of the gas coming into Europe thus appears in statistics as imports from the UK, even though its actual origin lies in LNG terminals on the other side of the Atlantic or in the Middle East. Europe has not gained a new producer, but a new intermediary.

The result of this change is a fundamental shift in the nature of energy dependence. It has not moved from one supplier to complete independence, but has spread across a whole network of routes, terminals, and hubs. The risks have not disappeared, they have only changed form.

The question is no longer just whether one supplier will decide to withhold gas, but also what will happen if there is a disruption in Norwegian production, if global demand for LNG drives up prices, or if key infrastructure fails.

Dependency has thus shifted from a single political link to a set of technical and market uncertainties that are more difficult to manage and even more difficult to predict. Today, the price of gas is not just a result of supply and demand, but a reflection of how Europe can cope with a combination of technical constraints, global competition, and geopolitical tensions.