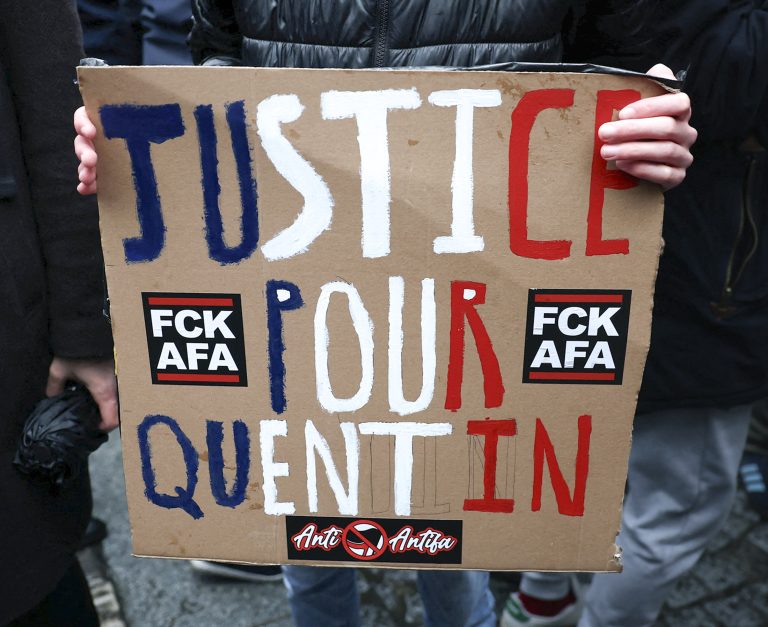

Lyon. On the evening of 13 February 2026, 23-year-old student Quentin D. was attacked on the margins of a political demonstration by a group of masked assailants. Around 20 individuals punched and kicked the young man, repeatedly striking his head. Quentin D. collapsed, was taken to hospital with severe injuries and died a few days later from massive brain trauma. French judicial authorities are investigating the case as suspected murder.

The attack took place in Lyon, France’s third-largest city, which for years has been regarded as a focal point for political street violence. Quentin D. was a practising Catholic, a mathematics student and had been active for two years within the right-wing Identitarian movement. The movement, which operates in several European countries, places cultural identity, national sovereignty and criticism of mass immigration at the centre of its ideology and describes itself as “metapolitical”. In France, it has long been under intense political and media scrutiny.

At the time of the attack, Quentin D. was present on the fringes of a right-wing counter-demonstration. The protest was directed against an appearance by Rima Hassan, a French–Palestinian lawyer and Member of the European Parliament for La France insoumise. Elected to the European Parliament in 2024, Hassan is regarded as a prominent representative of a radical left-wing, strongly pro-Palestinian and explicitly anti-Zionist political stance. Her public appearances regularly provoke protests and counter-demonstrations. The group was suddenly attacked by around 20 black-clad, masked assailants. Investigators believe the perpetrators acted in a coordinated manner. Several of them continued to kick Quentin D. even after he had fallen.

Video footage later circulated on social media shows the extreme brutality of the assault. The attackers then withdrew, leaving the severely injured student behind. The suspects are believed to come from the milieu of the far-left group “Jeune Garde Antifasciste”. The organisation describes itself as a militant anti-fascist structure that deliberately targets political opponents on the streets. It was considered particularly violent and was banned by French authorities in 2025. Nine individuals have been arrested in connection with Quentin D.’s death.

Between street violence and parliamentary politics

Among those detained is a parliamentary assistant to Raphaël Arnault, a member of La France insoumise. Arnault himself was among the founders of Jeune Garde in 2018. In this case, the link between parliamentary politics and militant street activism is therefore not merely ideological but personal. The President of the National Assembly has temporarily barred the assistant from access to Parliament.

The case unfolded during a period of pronounced political polarisation in France. The country’s party system has been deeply divided for years. On the right, the Rassemblement National, led by Marine Le Pen, regularly secures high vote shares in national elections but remains structurally disadvantaged by the majority voting system. In the 2024 parliamentary election, the party won the largest share of the vote but secured fewer seats than the left-wing bloc.

On the left, the so-called “New Popular Front” emerged in 2024, bringing together Socialists, Greens, Communists and the radical left under the leadership of La France insoumise. Despite receiving fewer votes than the Rassemblement National, the alliance became the largest parliamentary group. La France insoumise alone holds 72 seats and exerts considerable influence over political discourse. Party founder Jean-Luc Mélenchon has for years employed sharply polarising rhetoric, regularly describing political opponents as “fascists” or “enemies of the Republic”. This language has consequences. It contributes to the further brutalisation of political debate and extends well beyond the parliamentary arena.

Alongside this, France, like many Western countries, has a militant anti-fascist scene that sees itself as an extra-parliamentary bulwark against the right. Within this milieu, violence is often interpreted as a legitimate means of political confrontation. Clear political distancing has frequently been absent, not least because of ideological and personal overlaps.

The asymmetry of political violence

The political significance of Quentin D.’s death becomes particularly apparent by comparison. Had a left-wing student been beaten to death by masked right-wing extremists after a demonstration, a very different dynamic would likely have followed. International headlines, special news coverage, mass demonstrations, symbolic gestures and parliamentary initiatives would have been expected. The term “right-wing terror” would have dominated public discourse. Not only the perpetrators but entire political milieus would have come under suspicion.

In Quentin D.’s case, this escalation did not occur. Although the President of the National Assembly ordered a minute’s silence, restraint and relativisation otherwise prevailed. Politicians warned against “instrumentalisation” and pointed to the ongoing investigations.

This asymmetry is not accidental but reflects a deeper structural problem. In many Western political cultures, left-wing violence is still regarded as explicable, context-dependent or at least of secondary concern. Right-wing violence, by contrast, is treated – rightly – as a systemic threat. The problem arises when this distinction turns into a moral one-way street.

The death of Quentin D. demonstrates that left-wing violence is no longer confined to autonomous fringe groups. It operates within an ideological environment shaped in part by elements of institutional politics. When a parliamentary assistant is allegedly involved in a fatal attack, this is no longer an individual aberration but a structural warning sign. France’s Prime Minister described the incident as an “appalling tragedy”. President Emmanuel Macron stated that no ideology can ever justify killing. These statements reflect a broad consensus. Their political impact, however, remains limited as long as political violence continues to be assessed differently depending on its ideological origin.

Quentin D.’s death is therefore more than a criminal case. It exposes the selective manner in which Western democracies respond to political violence – and the blind spots that persist.