Amsterdam. From January 2028, the Netherlands will introduce a tax regime that remains unusual in Europe: private investors will be taxed not only on income actually received, but also on increases in the paper value of their assets – even where no sale has taken place. Presented technocratically as a move towards taxing “actual returns”, the reform represents a fundamental economic shift. The state will claim a share of book gains and tax value increases before they are realised. In doing so, it permanently alters the balance between private risk and public revenue – to the detriment of long-term personal investment.

The reform was triggered by a series of rulings by the Dutch Supreme Court beginning in 2021. Under the previous “Box 3” system, the government assumed notional returns on savings and investments and taxed those deemed profits regardless of actual performance. In a prolonged low-interest-rate environment, individuals found themselves paying tax on income they had never earned. The court ruled this unconstitutional, arguing that it violated property rights and principles of equal treatment.

The government therefore faced a dilemma: the old system was unlawful, yet interim arrangements and compensation measures cost the Treasury an estimated €2.3 billion annually. The new framework was intended to restore legal certainty while safeguarding fiscal stability. What has emerged is formally compliant with constitutional standards, but economically more problematic than its predecessor.

The reform also arrives at a moment of political transition. After the collapse of the coalition under Geert Wilders in the summer of 2025 and snap elections later that year, the country has since early 2026 been governed by a minority administration composed of the progressive-liberal D66, the liberal-conservative VVD and the Christian Democratic CDA. Rob Jetten of D66 is set to serve as Prime Minister. Minority governments operate under particular pressure to demonstrate fiscal discipline and administrative competence. A tax system that is straightforward to administer and guarantees predictable revenue aligns neatly with that objective. The choice appears driven less by ideology than by the imperative of financial consolidation.

Taxing value before liquidity

Dutch personal income tax is divided into three “boxes”, with Box 3 covering savings and investments. Under the new rules, all capital income actually received – interest, dividends and rental payments – will continue to be taxed in the year of receipt. In addition, however, the annual increase in the value of shares, bonds and cryptocurrencies will be treated as taxable income irrespective of whether those assets are sold.

The rate will be a flat 36 per cent. The previous tax-free capital allowance will be replaced by a tax-free annual return threshold of €1,800, and losses may be carried forward indefinitely, provided they exceed €500. Real estate and qualifying start-up shareholdings are excluded from the annual mark-to-market valuation and will continue to be taxed only upon disposal. The official justification is that otherwise serious liquidity problems would arise – a concern that is, notably, accepted in the case of financial portfolios.

The essential rupture lies in the separation of tax liability from cash flow. Consider a simplified example: an investor holds a diversified portfolio worth €250,000. In a strong year, its value rises by eight per cent to €270,000, generating a paper gain of €20,000. Tax due at 36 per cent amounts to €7,200. That sum does not exist as available cash. To meet the tax obligation, the investor must sell assets.

If markets subsequently fall by ten per cent, reducing the portfolio to €243,000, the investor has already liquidated part of their holdings to pay the prior year’s tax and now faces diminished wealth nonetheless. Losses may be offset in future years, but the liquidity has already left the portfolio. The mechanism is inherently pro-cyclical: in rising markets it adds selling pressure; in downturns it compounds losses. The state participates immediately in valuation gains but bears no symmetrical risk.

A structural imbalance

This establishes a structural asymmetry. Gains are taxed immediately; losses are merely carried forward. The state behaves like a shareholder with preferential access – without genuine exposure. Long-term capital formation depends on reinvestment, compounding and patience across market cycles. If capital must be sold annually to satisfy tax claims, the base for compounding shrinks. The effect is incremental but cumulative.

Over two or three decades, the difference may be substantial, as annual taxation of unrealised gains reduces not only liquidity but also reinvestment capacity. The state claims not merely income, but part of the growth trajectory itself.

Most European countries tax capital gains only upon realisation. Germany levies a flat 25 per cent withholding tax at sale; Norway, France, Austria and Italy follow comparable principles. Even jurisdictions with high marginal income tax rates refrain from taxing unrealised appreciation for private investors.

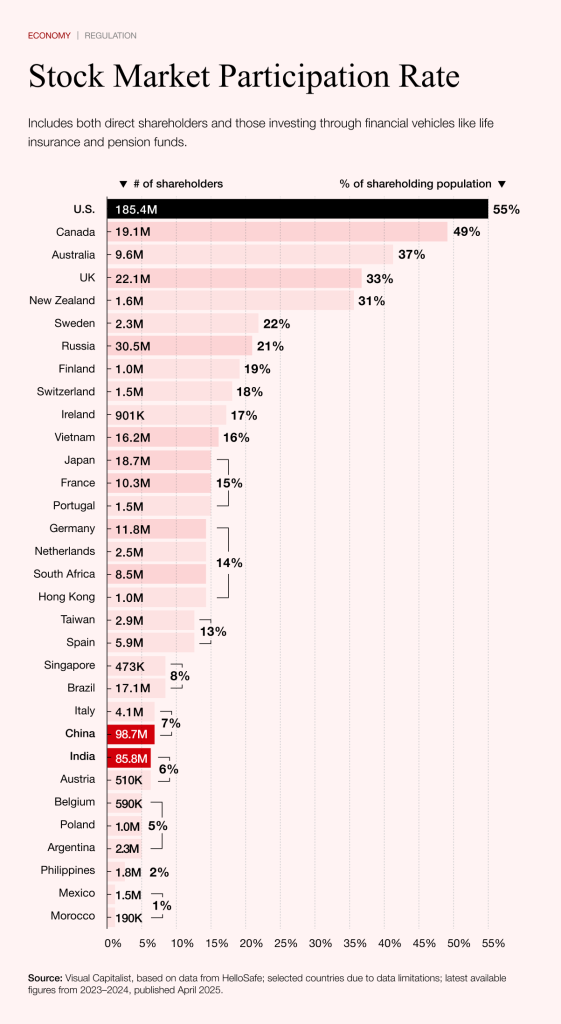

It is therefore striking that around 2.5 million Dutch citizens – roughly 14 per cent of the population – participate directly in the capital markets. While this places the Netherlands in the European middle range, Europe as a whole lags significantly behind the United States, where approximately 55 per cent of adults own shares, mutual funds or, increasingly, digital assets. Where the American system embeds equity ownership broadly across society, European participation remains comparatively modest. A reform that intensifies liquidity pressure risks discouraging an already limited investor base.

Capital mobility and the long-term consequences

The Netherlands has nevertheless chosen a different path. It effectively introduces an annual mark-to-market regime, treating investment portfolios as though they generate distributable income even when no distribution occurs. Administratively, the approach is efficient and fiscally predictable; from an investment policy perspective, it is far more contentious.

For larger fortunes, the reform may have tangible consequences, as mobile investors reconsider tax residence within the European Union’s freedom-of-movement framework. Holding structures or alternative vehicles outside Box 3 may become more attractive. Institutional investors are accustomed to such structuring; wealthy individuals likewise. The primary burden falls on the middle-class investor building wealth gradually through exchange-traded funds or individual shares, particularly where portfolio volatility magnifies liquidity risk.

Ultimately, the new Box 3 regime is not a marginal adjustment to tax law but a redefinition of the relationship between state and private capital. Risk remains entirely with the individual; revenue claims are secured early. Private provision through capital markets is not prohibited, but it becomes structurally more difficult – not through explicit restriction, but through liquidity strain.

The Netherlands sought a constitutionally secure tax system. What it has created is a model that combines legal certainty with structural capital extraction. The relevant question is not whether the system can function technically. It is how many investors will choose to remain under it.